This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Dollar Tree had been Unhedged’s best 2024 stock pick, up about 14 per cent. But it gave all that back yesterday, when it announced it was closing 1,000 of its 16,000 stores and taking a charge. We knew that store closures were a risk, and the shrink-to-grow decision looks smart, but knowing when a restructuring plan will pay off is tricky. Stock picking is hard. Send me your sob stories: robert.armstrong@ft.com.

Revisiting the bad bit of the economy

Well this doesn’t sound great:

We’ve talked pretty consistently [about how] it’s a challenging consumer environment. Consumers are working through . . . all the inflation that’s hitting their pocketbook . . . Higher interest rates are having an impact. I think in particular for lower-income consumers, you’ve got a couple of additional dynamics, eroded Covid savings that people were drawing on and spending from that are largely gone . . . you’re starting to see food-at-home inflation versus food-away-from-home getting back to its historical dynamic, which means some of those consumers are just choosing to eat at home more often

. . . [in] the informal eating-out sector, it’s certainly likely this year that we’re going to see negative traffic . . . from an industry standpoint because of those dynamics

That’s Ian Borden, chief financial officer of McDonald’s, speaking at an industry conference yesterday. This kind of talk might seem at odds with the consensus narrative about the economy. Growth and employment remain strong — so strong, in fact, that expectations for Federal Reserve interest rate cuts are being pushed further into the future. Inflation, while it refuses to get all the way to target, has come down a lot.

Borden’s comments came as enough of a surprise that McDonald’s shares fell almost 4 per cent on the day. But the shock should not be too great. There have been signs for a year or more that consumers at the low end of the income scale have not been fully participating in the boom (we have written about those signs, for example, here and here). What is notable is that these dreary signals have persisted even as general fear about recession have all but disappeared in the past few months.

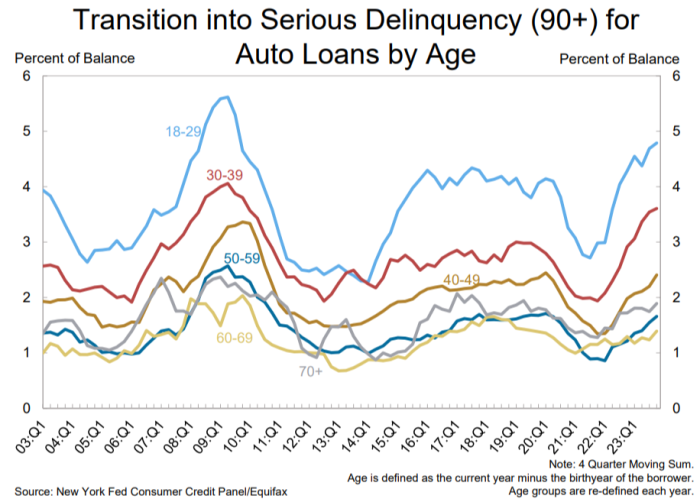

The split between the prosperous economy and the stresses on lower-income consumers is visible in the New York Fed’s chart of auto loan delinquency rates, split out by age:

Borrowers under 40, who are likely to have high debt relative to assets, are becoming delinquent at rates only just short of those seen at the height of the great financial crisis. Then, unemployment was 10 per cent; now it’s under four. This is still an unusual economy. If anything, given what we see in the delinquency data, it is surprising more companies are not making comments like Borden’s.

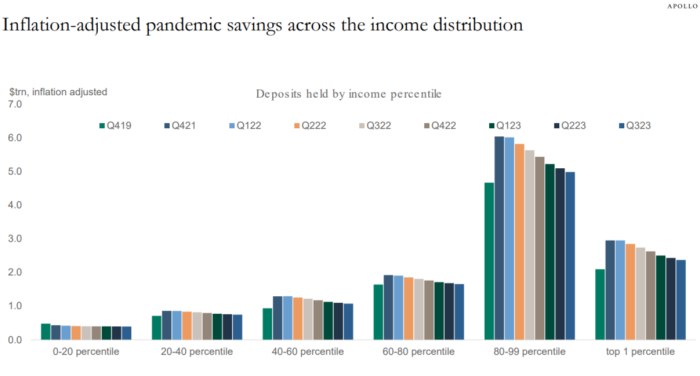

I should emphasise that I am not saying this in a the-good-news-is-fake-and-we-are-doomed kind of way. As Torsten Sløk of Apollo argued to me, most of the spending power in the economy is towards the upper end of the income spectrum, and those households have plenty of money on hand. There is a difference between unbalanced growth and unsustainable growth. His chart:

Companies that cater to the low-end consumer have felt some pressure already. Consumer staples stocks, as we have written, have moved sideways since May of last year and trail the market by more than 20 per cent. This is likely in part because staples outperformed in 2022 and the market had some catching up to do; and partly because many staples stocks are bond substitutes, which lose favour as bond yields rise; and partly because defensive stocks tend to underperform in risk-on rallies. But these factors are not the whole story. The low-end consumer will remain under pressure, especially if rates stay higher for longer because the wider economy continues to run hot. It will be surprising if Borden’s comments are not echoed by other companies exposed to the low-end consumer in the months to come.

Why JPMorgan is so dominant, part III: growth in context

In the past two days we’ve talked about JPMorgan’s dominant position in banking, how its diversified financial structure helped it grow, and how the bank has been part of a general trend of increasing returns to scale in banking. We’ve raised the question of how to best explain both increasing returns in banking in general, and JPMs rise to dominance in particular. Before answering that last question, though, I thought it might be good to be slightly more precise about the long-term growth rate of the industry, the biggest banks, and JPM.

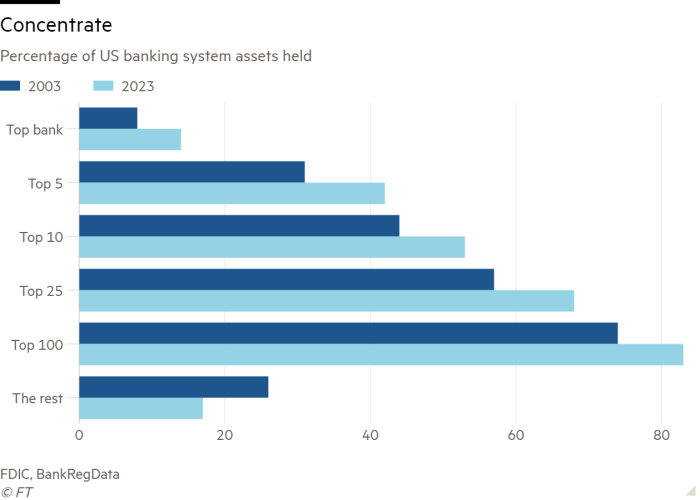

To do this, I looked at two time-slices of Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation data, from early 2003 and late 2023, using a data collection tool from BankRegData. The first point to make is that the increase in industry concentration over the past 20 years, as measured by assets, has been remarkable. Then, the top bank was Citi, and it had 8 per cent of the assets in the system; now it’s JPM, with 14 per cent. And there has been a general move of assets towards the bigger banks:

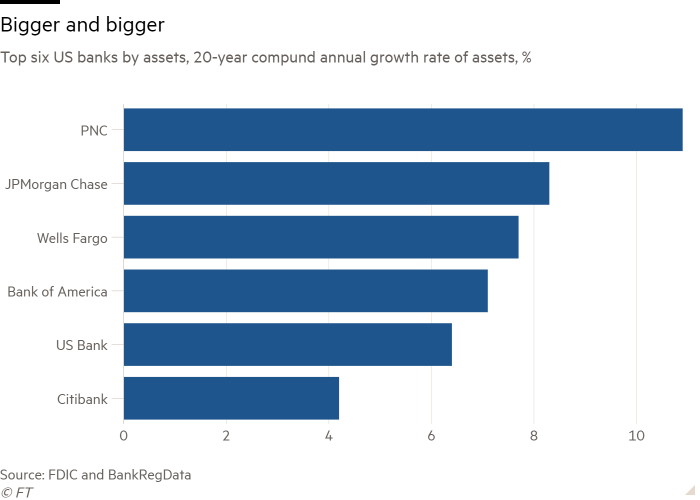

Over 20 years, assets in the US banking system have grown at 5 per cent a year. The top six banks have all done better than that — with the unhappy exception of Citi:

JPM, Bank of America, Wells and US Bank all outgrew the banking system despite being in the top ten by size back in 2003, too (PNC was number 22 then). The growth tailwind behind the big banks in the US is very clear.

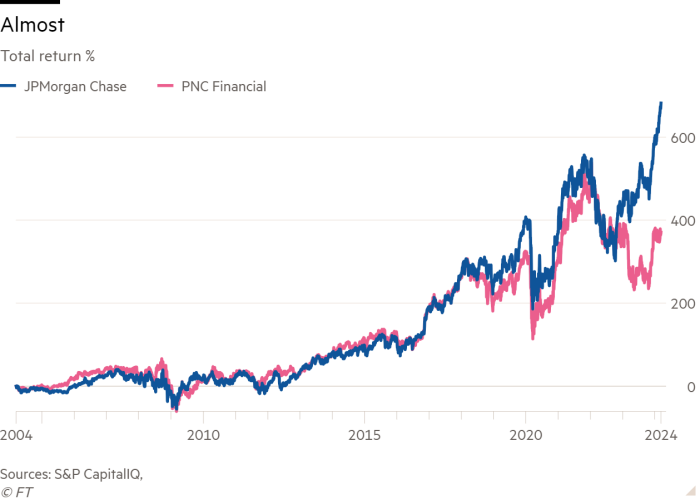

PNC, with its truly impressive growth, makes an interesting comparison with JPM. Despite being the number six US bank by size, it only has a sixth of JPMs assets. It is still basically a regional bank, albeit a big one. Yet for most of the past two decades PNC’s stock kept pace with JPM’s — until rates began to rise in 2022, and other regional banks started to struggle:

Safely compounding asset growth while earning a competitive return on equity is what makes bank stocks go up. That shares in PNC, a bank that has achieved exactly this over a long period, have struggled recently relative to JPMs suggests the advantages of scale in banking have only become stronger in the past few years.

Still, the core question remains: what, other than a favourable corporate structure, has allowed JPM to compound growth at a faster rate than even its very largest peers?

One good read

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.