Apart from learning the term, ‘Sephora kids’, pertaining to tweens taking to beauty products with a vengeance, the Nykaa founder-CEO seemed to me to be the best barometer of where India is heading today. No mean feat, sitting in the otherwise cabin’d, cribb’d, confined conditions of the here and now.

Till that evening, however, my association with Nykaa had been quite inapt, embarrassing, actually. Because of some form of acute phonetic dyslexia I seem to suffer from, I had always read – and pronounced – Nykaa, obviously the Hindi for ‘heroine’, as the Bengali word, ‘nyeka’.

Considered pretty much an untranslatable word like ‘abhimaan’, and susceptible to misinterpretation like the recent petit spat on the election campaign theatre over ‘shakti’ (power) and ‘Shakti’ (female divinity), nyeka roughly and unreadily translates to someone with affectations, a person who pretends to not know or understand something when he or she actually does, or generally someone insufferable because of his or her overblown, florid way of speaking.

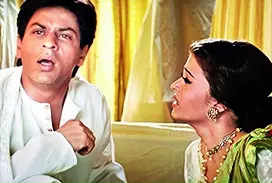

Nyeka is also an odd word, considering that its bearer is usually, but not always, accused of being hyper-feminised, if not effeminate, while at the same time, the word is gender-neutral in that a man or woman can be equally accused of being engaged in nyekami (affectatious behaviour). This may originate from something far older than Aishwarya Rai’s meme-worthy, blush-attack ‘Eesh’ in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s 2002 adaptation of Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s (equally nyeka?) 1917 novel, Devdas. Some lingering Bengali ethnic shame may be at play here.

19th century one-man think-tank and policymaker Thomas Macaulay – he was author of ‘Minutes on Education in India’ (1835) that was primarily responsible for introducing Western institutional education in India as a ‘civilisational mission’ – found the upper-class male Hindu Bengali babu to be the archetypal nyeka. Without using the N-word, he wrote, ‘The physical organisation of the Bengalee [sic] is feeble even to effeminacy. He lives in a constant vapour bath. His pursuits are sedentary, his limbs delicate, his movements languid. During many ages he has been trampled upon by men of bolder and more hardy breeds. Courage, independence, veracity, are qualities to which his constitution and his situation are equally unfavourable…. [He] would see his country overrun, his house laid in ashes, his children murdered or dishonoured, without having the spirit to strike one blow.’ It’s another matter that within half a century, Bengali revolutionaries of the non-non-violent variety would force the British Raj to move its capital from Calcutta to New Delhi. But the sting of the caricature remains today in pop culture, whether in nyeka characters with sing-song voices, or pretentious hyper-Anglicised (‘No, yaaa, I simply can’t bear another G&T in this horrrrid weather) and/or hyper-Bengalicised men and women who break into Rabindrasangeet at a drop of a sola topee.

The 21st century ‘nyeka’ person is seen as wearing a permanent pout, is self- and selfie-obsessed, and has been made infamous in Bengali culture by the famous riposte of ‘Nyaka!’ to the imploration of ‘Shey tho eka’ (But he is alone) by Satyajit Ray in his 1980 political satire, Hirak Rajar Deshe (In the Kingdom of Hirak). The term was used more recently in 2019 as a blunt instrument by Mamata Banerjee to describe former West Bengal governor and current vice-president Jagdeep Dhankhar, without naming him, for his constant criticism of her government.

Nyeka has somewhat the same flavour that ‘woke’ has in putting down hyper-sensitive, self-righteous and faux humble behaviour. Effectively, it conjures up the exact opposite of the no-nonsense, self-made billionaire Falguni Nayar and her very differently spelt and pronounced creation, Nykaa. I happily stand corrected.