Roy Jenkins, a former UK finance minister and EU Commission president, once described inheritance tax as a “voluntary levy,” paid only by those who distrust their heirs more than they dislike the tax authorities.

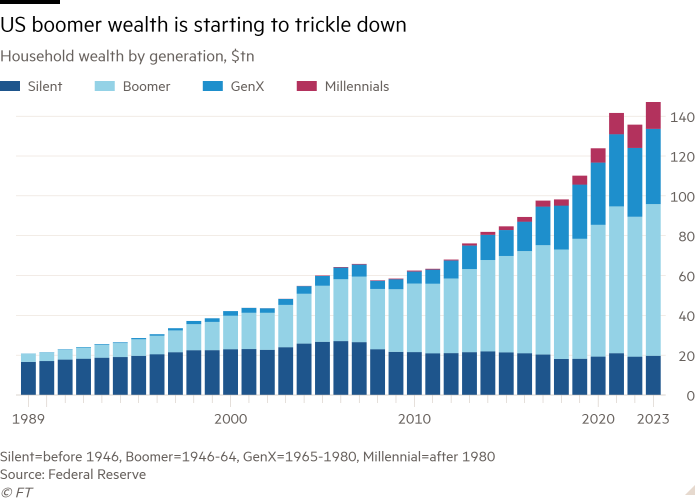

But as baby boomer wealth starts to trickle down to younger cohorts, and with government coffers around the world strained by the costs of the pandemic and ageing populations, debate is growing about whether it should become, at the very least, less voluntary.

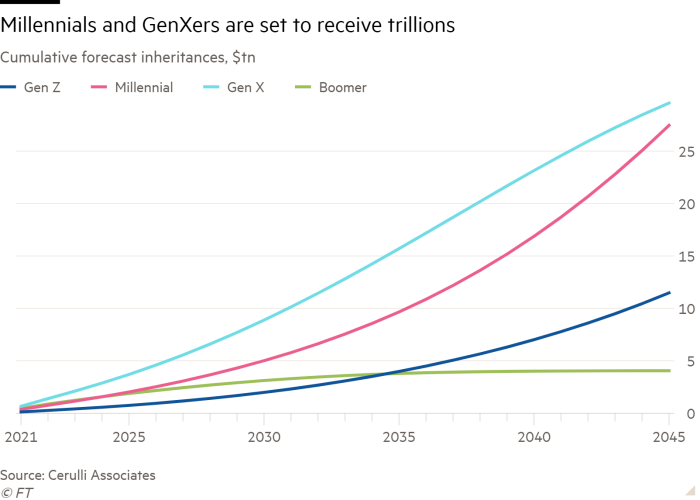

By 2045, around $90tn in the US alone is set to be transferred from those born before 1964 to their heirs, according to research by Cerulli Associates. Many argue that governments should target that wealth rather than taxing the incomes and consumption of younger generations often struggling with higher education and housing costs.

Gabriel Zucman, professor of economics at the Paris School of Economics and at the University of California, Berkeley, whom the G20 has asked to examine a proposal for a co-ordinated minimum tax on the super-rich, argues that “there are massive public needs for healthcare, education or for fighting climate change.”

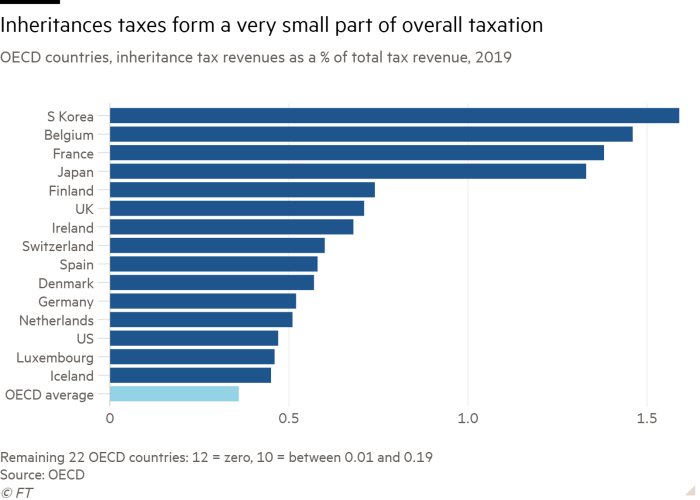

Wealth taxes in general, and inheritance taxes in particular, currently collect very little revenue. But Lucas Chancel, co-director of the World Inequality Lab and Professor at Sciences Po and Harvard Kennedy School, says they are important “because they help prevent the reproduction of inequalities from a generation to the next and have the power to raise money for public goods”.

“What is the justification that one person is born with €100mn because that person inherited, and another person is born with €0?” he asks.

Such arguments have growing salience given increasing debate about intergenerational equality and the growth in the ranks of the super-wealthy.

Alex Cobham, chief executive of the Tax Justice Network, a UK campaign group, says the baby boomer generation — generally taken to mean those born between 1946 and 1964 — have been unusually fortunate in terms of wealth accumulation. Part of that has been due to “state and economic factors in which they had no individual role”, he adds.

Swiss bank UBS, one of the world’s biggest wealth managers, estimated last year that the 1,023 billionaires around the world aged 70 or over had a combined worth of $5.2tn.

It also found that in 2023 more new billionaires were created through inheritance than through entrepreneurship for the first time since its annual survey began in 2015.

“[Inheritance] . . . is clearly becoming an increasingly material factor in the creation of new billionaires,” the report said.

But inheritance taxes are politically difficult, despite their limited reach, partly because voters feel strongly that the bequests they make to their children are none of the government’s business.

Experts warn that higher estate taxes alone are unlikely to mend state finances and will do little to address inequality, either between generations or within them. But they could result in forced asset sales that disrupt orderly markets and create disincentives to save, invest or take risks.

“An inheritance tax doesn’t fix the core problem: an economy that’s in decline and an ageing population,” says Aswath Damodaran, professor of finance at the Stern School of Business at New York University.

“You’re robbing Peter to pay Paul — and not even to pay Paul, but to pay Paul’s son because Paul didn’t save.”

With even the youngest boomers turning 60 this year, the wealth transfer is already under way — leaving policymakers facing increasingly urgent questions about whether and how to influence the outcome. Their responses could shape tax policy for many years.

Inheritance taxes date back to the Roman empire, far longer than more recent arrivals such as income tax. But they have been in retreat since the 1970s.

Sweden, Canada, Australia and New Zealand are among the countries to have scrapped them completely. The OECD’s most recent comparative study, published in 2021, found inheritance taxes in 2019 accounted for just 0.5 per cent of total tax revenues on average across the countries that levy such taxes, down from 1.1 per cent in 1965.

“As recently as 1976, the US estate tax applied to more than 7 per cent of all descendants at a top rate of 70 per cent,” says Gabriela Sandoval, executive director at the Excessive Wealth Disorder Institute, a US-based pressure group. By 2019, she adds, that had shrunk to just 0.07 per cent of descendants, a level that “allows for the concentration of wealth in very few hands”.

Bill Gale, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and co-director of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, says changes introduced by President Donald Trump in 2017 “eviscerated the wealth inheritance tax system” in the US. “The estates threshold was raised to very high levels and there are various ways to avoid it.”

Inheritances in the US are taxed only if they exceed $13.61mn. Although this is an outlier, high thresholds make inheritance taxes less effective across the world, according to the OECD.

The group’s report said better-designed inheritance taxes could help raise revenue and enhance equality at lower economic cost than alternative taxes. It suggested they should have lower thresholds, fewer exemptions, apply to recipients rather than the deceased’s estate, and have progressive rather than flat rates.

Others say more fundamental reforms are required. Thomas Piketty, the French economist whose 2013 book Capital In The 21st Century helped reinvigorate the debate about wealth taxes, has championed the idea of “inheritance for all”. He says universal distributions are needed to address a long-term “hyper-concentration of property”.

In a recent blog post in Le Monde, he noted that the poorest 50 per cent own 5 per cent of total wealth in France, with the richest 10 per cent owning 55 per cent. “The idea that we just have to wait for wealth to spread doesn’t make much sense: if that were the case, we would have seen it long ago.”

He proposes paying a flat sum of around €120,000 to everyone when they turn 25, with the funds to provide this money coming from a mix of progressive wealth and inheritance taxes that together account for around 5 per cent of GDP.

Reimagining inheritance taxation is not confined to those on the left. Lord David Willetts, a British Conservative peer and president of think-tanks the Intergenerational Centre and the Resolution Foundation, advocates giving all British 30-year-olds a £10,000 “citizens’ inheritance.”

The cash grant would be restricted to four specific uses: funding education and training or paying off tuition fee debt, deposits for rental or home purchases, investment in pensions and start-up costs for new businesses.

Willetts says such payments are needed to help current generations achieve what their parents did. “Would Thatcher have wanted a society where inheritance mattered so much and acquiring wealth with your earnings was so difficult?” he asks, referring to former UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher.

“I want to see people have a stake in society,” he adds. “There are many people now in the middle who feel more like the precariat and who don’t feel like they are going to have the basic provision of owning their own flat and a funded pension.”

He argues that such distributions could be funded by reforming the UK’s current regime of taxing estates to one that taxes recipients on the value of gifts received at any stage of their lives.

Pascal Saint-Amans, a former head of tax at the OECD, describes inheritance levies as “the most underrated tax”, especially when compared with wealth taxes levied periodically on the assets of the living.

Several countries have repealed these in the past few decades, notably France, which concluded that its impôt sur la fortune was expensive to administer, open to abuse and caused many wealthy people to leave the country. It was scrapped by President Emmanuel Macron in 2017.

“A wealth tax is a false ‘good idea’,” Saint-Amans adds. “The tax which actually is the answer, and that doesn’t have the same constraints, is inheritance tax.” It is relatively easy to collect as the assets of the deceased can be partially liquidated to meet the cost.

Saint-Amans thinks it would make sense for countries to apply a global minimum tax on inheritances for billionaires in particular. He says increased international tax co-operation, which has led to the end of bank secrecy and the automatic sharing of financial information between countries, would make it hard to avoid such a levy.

He says the template for getting international co-operation for such a policy would be the 15 per cent minimum corporate tax rate agreement introduced earlier this year. This was brokered by the OECD and agreed to by more than 140 countries, although the world’s largest economies, the US and China, have yet to ratify it.

In 2007, the UK’s then shadow chancellor, George Osborne, promised that the Conservatives would raise the inheritance tax threshold to £1mn if they were elected.

The public response was so positive that the then prime minister, Labour’s Gordon Brown, decided against calling a snap general election. It is a lesson no politician dares forget: inheritance taxes, for all their limited reach, are unpopular.

An Ipsos Mori poll last year found that 43 per cent of respondents considered them “unfair” even though fewer than 5 per cent of UK estates are liable for them.

Another poll, for UK-based think-tank Demos last year, found that 16 per cent of over-65s would be more likely to support the ruling Conservative government if it pledged to abolish inheritance tax, against 10 per cent who would be less likely. Support among 18- to 34-year-olds would decline by a net 1.5 percentage points — but older people are on average more likely to vote.

Dawn Register, head of tax dispute resolution at BDO, an accountancy firm, says there is “a lot of emotion around [inheritance tax] as it’s linked to someone’s death”.

Others put its unpopularity down to the lobbying and influence of the super-rich. “The whole issue is whether we’re focusing on the moderately wealthy — the small business owner, the farmer, the woman who’s had a good career — or whether we’re focused on the billionaire,” says Gale.

“The billionaires who don’t want to pay taxes want [us] to focus on the small guy, who is a much more sympathetic figure.”

Chancel suggests that calls for inheritance tax reform should make it very clear that “the middle and working class” would be shielded from having to pay anything more. “It’d be useful to talk about super inheritance taxes instead,” he adds.

But for some, the opposition is more deep-seated and visceral than that. “It’s all about the kids,” Saint-Amans says. “Why do you live on earth? To leave a legacy. And here you have the government meddling with your legacy.”

Willetts agrees with the “noble instinct” for people to wish to provide for their children. “But as well as being good parents, we have to be good citizens.”

Critics say there are other reasons why inheritance tax is regularly cited as the most unpopular tax.

Kyra Motley, partner at law firm Boodle Hatfield, points to the practicalities of the administration process in the UK. “People don’t like the fact you’ve got to sell mum and dad’s house before you pay it,” she says. “You can have heirs inheriting a modest amount of money and finding themselves in a lot of difficulty.”

Others have more philosophical objections. “You’re taxing income that’s already been taxed, so fundamentally it’s being double-taxed,” says Stern’s Damodaran, though this argument could apply to many sales and consumption taxes too.

Will McBride, vice-president of federal tax policy at the Tax Foundation, a US think-tank, says that inheritance tax “deters savings, investment, work — all the things that we have long understood contribute majorly to economic growth.”

“In the longer term, it will lead to a slowing down of the economy and reduce dynamism to a degree,” he adds. “The main upside is for politicians to use it as a rallying cry.”

He cites research suggesting Denmark’s famously generous welfare and education policies, funded through high public taxation, have had limited impact upon equality and social mobility.

“Inequality will continue and has continued despite the proliferation of inheritance taxes. To address inequality, we need to think about this more broadly, not just using tax instruments,” McBride adds.

Not everyone has confidence that the state is better suited to deciding how hard-won assets should be distributed in the form of “inheritance for all” type measures.

Damodaran says that in order to accept the idea of universal handouts, “you’ve got to be OK with nobody saving and the government acting as the pension fund or wealth creator of last resort.”

“My concern is the message that would send to the next generation is abysmal, in that they do not need to take personal responsibility.”

As a father of four grown children, he says he understands the struggles younger generations face to build wealth, particularly through home ownership. But he argues it would be better for governments to target help at increasing access to home ownership than providing blanket inheritances.

“I don’t think you develop a wealth mentality overnight . . . until you go through those acts of saving in things that build up — a house, investments, stocks,” he says.

“It’s easy to blame the boomers. A lot of young people don’t have the savings mindset.”