Business reporter

Gonzalo Rojas

Gonzalo RojasA proposed law in Colombia’s Congress seeks to ban the sale of merchandise that celebrates former drug lord Pablo Escobar. But opinions are divided on it.

On Monday, 27 November 1989, Gonzalo Rojas was at school in the Colombian capital of Bogota when a teacher pulled him out of class to deliver some devastating news.

His father, also called Gonzalo, had died in a plane crash that morning.

“I remember leaving and seeing my mum and grandma waiting for me, crying,” says Mr Rojas, who was just 10-years-old at the time. “It was a very, very sad day.”

Minutes after take off, an explosion on board Avianca flight 203 killed the 107 passengers and crew, as well as three people on the ground who were hit by falling debris.

The blast wasn’t an accident. It was a deliberate bomb attack by Pablo Escobar and his Medellín cartel.

While an era defined by drug wars, bombings, kidnappings and a sky high murder rate has largely been relegated to Colombia’s past, Escobar’s legacy has not.

The notorious criminal, who was killed by security forces in 1993, has achieved a near cult-like status around the world, immortalised in books, music and TV productions like the Netflix series Narcos.

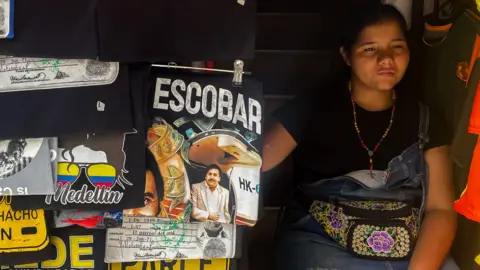

In Colombia itself, his name and face are adorned on mugs, keychains, and t-shirts in tourist shops catering mainly to curious visitors.

But a proposed law in Colombia’s Congress is seeking to change this.

The bill wants to ban Escobar merchandise – and that of other convicted criminals – to help put an end to the glorification of a drug boss who was central in the global cocaine trade and widely held responsible for at least 4,000 killings.

“Difficult issues that are part of the history and memory of our country cannot simply be remembered by a T-shirt, or a sticker sold on a street corner,” says Juan Sebastián Gómez, Congress member and co-author of the bill.

The proposed law would prohibit the selling, as well as the use and carrying of clothing and items promoting criminals, including Escobar. It would mean fines for those who violated the rules, and a temporary suspension of businesses.

Catherine Ellis

Catherine EllisMany vendors selling the goods claim a law prohibiting this merchandise would harm their livelihoods.

“This is terrible. We have a right to work, and these Pablo T-shirts especially always sell well,” says Joana Montoya, who owns a stall stocked full of Escobar merchandise in Comuna 13, a popular tourist zone of Medellín.

Medellín, Escobar’s hometown, was known as “the most dangerous city in the world” in the late 80s and early 90s due to violence associated with drug wars and Colombia’s armed conflict.

Today it’s been revitalised into a hub of innovation and tourism, with vendors eager to cash in on the influx of visitors wanting to take home souvenirs – some related to Escobar.

“This Escobar merchandise benefits many families here – it sustains us. It helps us pay our rent, buy food, look after our kids,” says Ms Montaya, who supports herself and her young daughter.

Ms Montoya says at least 15% of her sales come from Escobar products, but some sellers tell the BBC that for them it’s as much as 60%.

Catherine Ellis

Catherine EllisIf the bill is approved there would be a defined time period for sellers to familiarise themselves with the new rules and phase out their Escobar stock.

“We’d need a transition phase so that people could stop selling these products and replace them with other ones,” explains Congressman Gómez. He says that Colombia has more interesting things to show than drug lords, and that the association with Escobar has stigmatised the country abroad.

Some of the T-shirts, sold for around £5, bear a catchphrase linked to Escobar – “silver or lead?”. This symbolises the choice the cartel boss gave to those who posed a threat to his criminal operations: accept a bribe or be killed.

Shop assistant María Suarez believes that the profit gained from sales of Escobar merchandise isn’t ethical.

“We need this ban. He did awful things and these souvenirs are things that shouldn’t exist,” she says, explaining that she feels uncomfortable that her boss stocks Escobar items.

Escobar and his Medellín cartel at one point were believed to have controlled 80% of the cocaine entering the US. In 1987, he was named as one of the richest people in the world by Forbes magazine.

He spent some of his fortune developing deprived neighbourhoods, but many people consider this as a tactic to buy loyalty from some segments of the population.

Years on from his father’s death, Mr Rojas remembers him as a calm and responsible man, who loved his family. For him, the bill is a defining moment.

“It’s a milestone in the road about how we reflect on what is happening in terms of the commercialisation of images of Pablo Escobar in order to correct it,” says Mr Rojas.

Yet he does have criticisms about the proposals. He believes the bill doesn’t focus enough on education.

Juan Sebastián Gómez

Juan Sebastián GómezMr Rojas recalls a day many years ago when he met a man wearing a green T-shirt with a silhouette of Escobar, and the words “Pablo, President”.

“It caused me such confusion that I wasn’t able to say anything to him about it,” he says.

“There needs to be more of an emphasis on how we deliver different messages to new generations, so that there isn’t a positive image of what a cartel boss is.”

Mr Rojas has actively been involved in efforts to reshape narratives around Escobar and the drug trade. Along with some other victims, he launched narcostore.com in 2019, an online shop that appears to sell Escobar-themed items.

But none of the products actually exist and when customers select an item they are shown a video testimony from a victim. Mr Rojas says the site has attracted 180 million visits from around the world.

In Colombia’s Congress, the bill faces four stages it needs to pass before it can become law. Gómez says he’s hoping it sparks reflection both inside and outside of Congress.

“In Germany you don’t sell Hitler T-shirts or swastikas. In Italy you don’t sell Mussolini stickers, and you don’t go to Chile and get a copy of Pinochet’s ID card.

“I think the most important thing the bill can do is to generate a conversation as a country – a conversation that hasn’t happened yet.”

Medellín’s mayor – who was also a presidential candidate in the 2022 elections – has publicly backed the bill, calling the merchandise “an insult to the city, the country and the victims”.

In El Poblado, an upmarket area of Medellín popular with tourists, three Americans browse a stall brimming with souvenirs. One buys a cap with Escobar’s name and face printed on the front. He says he wants a memento of “history”.

But for supporters of the bill, this isn’t about removing Escobar from history, it’s about erasing a mythical construct of him, fostering new ways to honour the victims he killed – and acknowledging the lingering pain of victims left behind.