In early 2023, Ajit Jain was weighing Berkshire Hathaway’s exposure to the risk of a devastating hurricane hitting Florida.

If its insurance business took on more cover and the upcoming season proved tame, Berkshire would reap a multibillion-dollar windfall. The downside? A potential $15bn in losses if it turned into an ugly year for natural catastrophes. Jain sought permission from his boss, Warren Buffett, to increase the bet.

“Warren said yes without even listening to what the numbers were,” Jain recounted to shareholders at Berkshire’s annual meeting last year. With the season ending up a mild one, the decision helped propel the insurance business to one of the best underwriting profits in its history.

The 72-year-old Jain heads the insurance operations that underpin Berkshire, providing the cheap capital that has allowed Buffett to build a conglomerate rare in American history, owner of businesses from Duracell batteries to railroad operator BNSF and one of the biggest investors in the US stock market.

This article is the second in a series on what Berkshire may look like when Buffett no longer has the reins, and examines the insurance business, drawing on accounts of current and former employees, competitors and advisers. Berkshire declined to put executives, including Jain, up for interviews.

Buffett takes a firmly hands-off approach to Berkshire’s businesses, but makes an exception for insurance, which spans Geico, the National Indemnity Company, and vast reinsurance operations, including Gen Re. For years Buffett and Jain had a daily call, according to people familiar with the matter.

“They are both singular geniuses, there are no ifs or buts about that,” Thomas Gayner, chief executive at insurance and investment group Markel, itself a Berkshire shareholder, said of Buffett and Jain.

A Berkshire board member since 2018, Jain was once tipped as a possible chief executive of the conglomerate before Buffett in 2021 anointed Greg Abel, another long-serving lieutenant, as his successor. But Berkshire shareholders and industry executives say Jain’s record — and the critical role of the insurance business — arguably make him the most important person at the company after Buffett.

Already beyond the standard retirement age, Jain, a vegetarian and teetotaller, has given no indication of when he might step down. But with Charlie Munger, who helped build Berkshire, dying last November, and Buffett turning 94 in August, Jain’s future and that of the insurance operations have assumed more importance.

“He’s a very important player,” said a person who has worked with Buffett for years. “Ajit is the person that is by far the most trusted . . . He’s made a shit ton of money for the company.”

Buffett’s fascination with the insurance industry dates back more than 70 years. In 1951, he penned a column, “The Security I Like Best”, and picked Government Employees Insurance Company, or Geico, then chaired by his mentor at Columbia University, the famed investor Benjamin Graham.

Berkshire would acquire Geico, a motor insurer, in 1996, expanding its operations that began in 1967 with the purchase of National Indemnity, an Omaha-based property and casualty insurer. Its last significant deal came in 2022 with the $12bn acquisition of Alleghany, an insurance-to-manufacturing group.

Buffett was among the first to work out that the premiums American consumers and businesses paid to the likes of Geico and National Indemnity, and held to pay claims, were low-cost capital, financial firepower that could be profitably invested over decades.

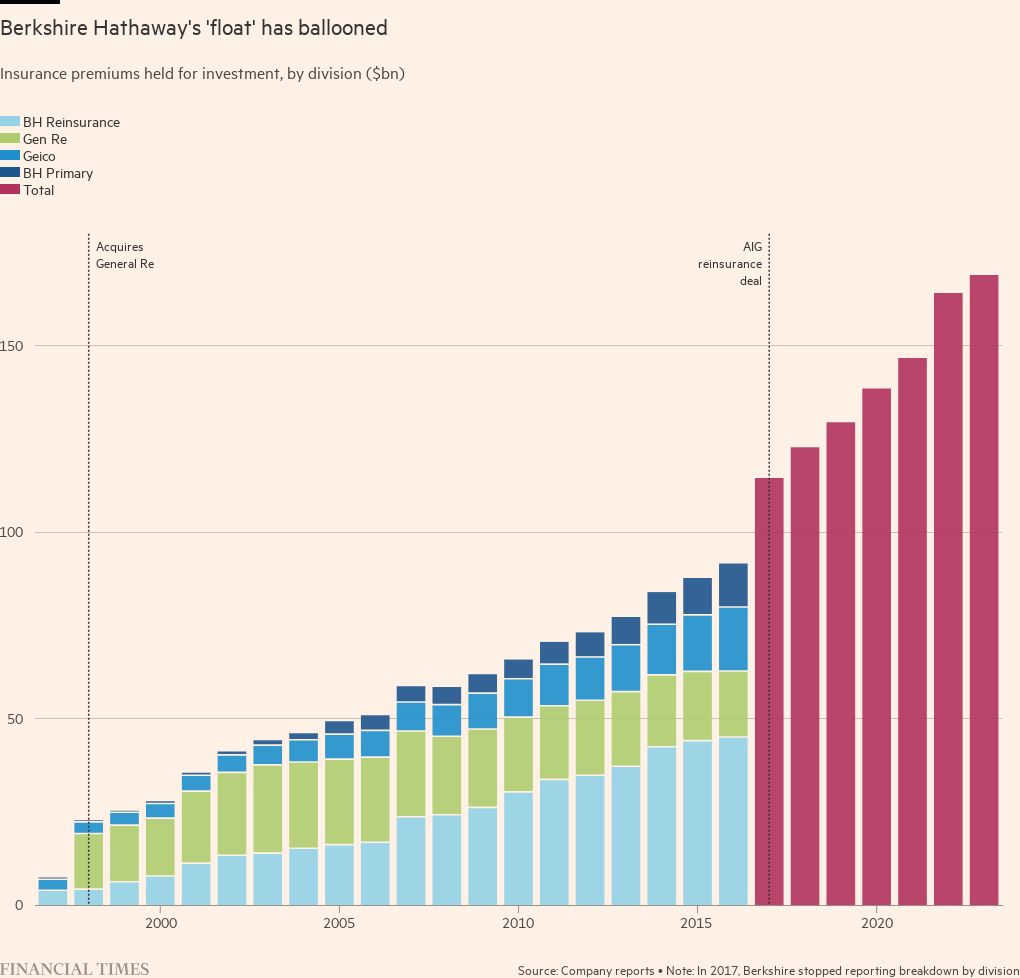

The float, or the money Berkshire takes in as premiums, holds to pay claims and invests, has ballooned from $39mn in 1970 to $169bn last year.

In contrast to rival insurers, which chiefly invest their premiums in fixed-income securities such as Treasuries and corporate bonds, Buffett has for decades ploughed money into stocks, a strategy that has proved a boon for Berkshire shareholders. It is enabled by the group’s $1tn balance sheet, which allows it to stomach the higher risk.

Berkshire’s model also sidesteps the perpetual threat hanging over many other investors: the need to raise new funds while facing redemptions if returns are poor.

“He was able to underwrite with discipline, invest the capital as required by regulators . . . and then have enough left to invest it in stocks, and the acquisition of businesses, [and] do each of those things with not just discipline but a kind of brilliance,” said Lawrence Cunningham, an emeritus professor at George Washington University, who has written books on Berkshire. “It’s that triple execution that was a unique feat. No one has ever done it at that scale.”

It is Jain who is credited with the underwriting skills that have so far avoided a blow-up that would have imperilled the model at the heart of the conglomerate.

Many of the contracts Jain, who grew up in India and joined Berkshire from consultancy McKinsey in 1986, is responsible for are large and fiendishly complicated, such as a banner $7bn reinsurance deal with Lloyd’s of London in 2006 over asbestos claims.

They often leave Berkshire liable for making a payout years or even decades after a policy was initially signed. Given most are very difficult to get out of, a misjudgment could be a drag on Berkshire’s underwriting profits for years.

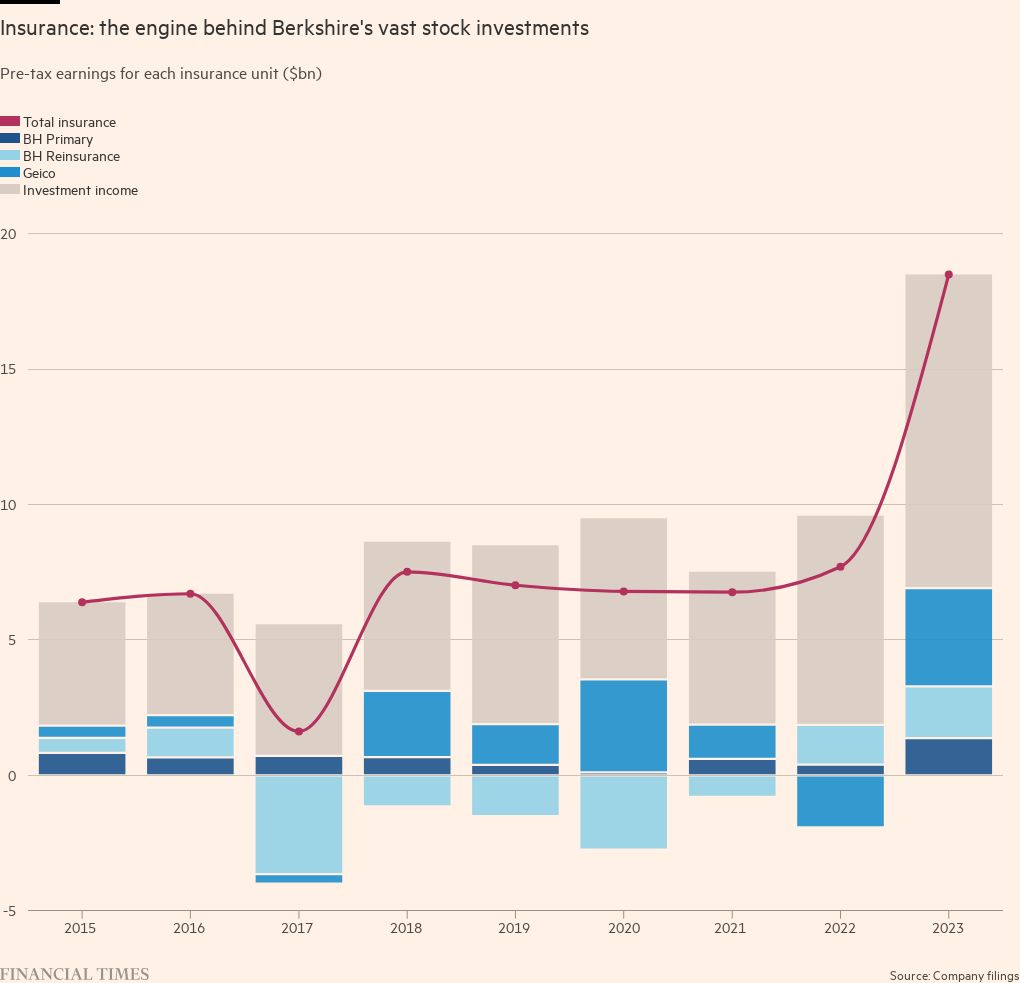

Jain has taken advantage of Berkshire’s balance sheet to turn it into the market’s reinsurer of last resort, taking on risks from other firms at a handsome price. Berkshire’s insurance underwriting divisions have been profitable for 18 of the past 20 years, according to the group’s latest filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Whenever Jain does retire, his successor will inherit a market that has recently seen buyout groups, including Apollo, KKR and Blackstone, push into it, creating a new breed of insurance-investment empires with expertise in areas such as private credit. For now, most of the firms have largely focused their attention on the annuities business, but some expect them to expand their footprint beyond that into areas where Berkshire has long operated in.

“The private capital industry is very innovative,” said one former Berkshire executive. “If there is a way to make money they’ll figure it out.”

Geico, meanwhile, has ceded market share in recent years, with analysts saying it has been slower than some rivals such as Ohio-based Progressive to adopt technology that is changing how motor insurance is underwritten, including telematics. Telematic technology tracks your driving and can reward safer drivers with lower premiums.

“Buffett is not bulletproof,” said one former manager at the conglomerate.

Despite new threats, industry executives say the biggest question facing Berkshire can be boiled down to a simple one: will the group be able to replace Jain’s ability to calibrate risks and his appetite to take big and sometimes contrarian bets?

According to people familiar with the matter, the contenders to replace Jain include Peter Eastwood, who runs the fast-growing Berkshire Hathaway Specialty Insurance unit, and Charlie Shamieh, chair of Gen Re, a reinsurer Berkshire acquired in 1998. Todd Combs, one of Buffett’s two investment deputies and who became chief executive of Geico in 2019, was also in the running, the people said.

Geico and Berkshire Hathaway Specialty Insurance declined to comment. Gen Re did not respond to requests for comment.

The chief executive of a rival insurer who knows the trio said they were “very good at what they do, they’re good at their verticals”, but running the entire operations would be a significant step up.

Joe Brandon, a former chief executive of Gen Re, has also been mooted. Brandon returned to the Berkshire fold in 2022 through the acquisition of Alleghany, which he leads. Insiders and former advisers to Berkshire say his path to succeed Jain could be complicated by the manner of his exit from Gen Re in 2008 following a fraud scandal that saw four employees charged. Brandon, who co-operated with investigators and was not charged, declined to comment.

Jain, described by one former employee “as a sweetheart” but “tough as nails” if you’re negotiating against him, masterminded the deal in which Berkshire took over legacy asbestos and other long-term claims that threatened to ruin Lloyd’s.

John Neal, the chief executive of Lloyd’s, said Jain’s record made him one of the “few people who have earned the right to make those bold decisions”.

Jain and his colleagues often scale back the amount of cover they provide when they judge the risk outweighs the price they can command. While this can lead to fallow underwriting years, it means the business can move at speed when pricing improves, say industry experts.

It is an advantage not shared by traditional reinsurers, which face greater pressure from shareholders to consistently expand their underwriting.

“[Jain] has a massive balance sheet, with a very low expense ratio, which enables him to jump in and out of the marketplace in the way that others can’t,” said Stephen Catlin, insurance industry veteran and the executive chair of London-based insurer Convex.

While Geico is the better-known brand, it is National Indemnity that is at the centre of Berkshire’s insurance operations.

Within the industry, the unit is regarded as opaque. Apart from high-profile deals in which the Berkshire name is deliberately publicised, such as a 2017 transaction in which AIG paid it $10bn to take on some long-term commercial risks it had underwritten, it is hard to discern its footprint in the market.

“I think people underestimate the deals they do because they only see the deals they see,” said Neal of Lloyd’s.

It has also long been one of Buffett’s preferred acquisition vehicles. When Berkshire bought BNSF in 2010, it was National Indemnity that executed the transaction.

Much of Berkshire’s $354bn stock portfolio is held by the unit, including a large part of its stake in Apple, its holding in oil producer Occidental as well as the multibillion-dollar investments it made in 2020 in five Japanese trading houses, including Mitsubishi and Mitsui. It was also the vehicle Berkshire used to buy Pilot Flying J, a truck-stop operator.

According to filings with insurance regulators reviewed by the Financial Times, the unit ultimately bears much of the risk that individual Berkshire insurance subsidiaries take.

Last year, it struck reinsurance agreements with some of the insurance units Berkshire acquired as part of its takeover of Alleghany, taking on 50 per cent of their possible claims in exchange for more than $5bn in loss reserves the units had set aside. It also struck deals to take on a quota of the premiums they write in the future.

“The large capital base of National Indemnity and the broader Berkshire allows the group to take on more investment risk than is typical for insurance companies,” said Bruce Ballentine, senior credit officer at rating agency Moody’s.

Berkshire also has an $18bn credit line with National Indemnity, allowing it to borrow billions of dollars should Buffett need to move quickly to tap capital.

The filings also showed a series of dividends between Berkshire’s subsidiaries and National Indemnity, as well as the parent company itself. Late last year, National Indemnity transferred its ownership of BNSF to Berkshire in a deal that valued the railroad at $82bn. National Indemnity declined to comment.

National Indemnity was the business Jain ran for years before being promoted to vice-chair of Berkshire in 2018, when he took control of the entire insurance operations.

Buffett has long said that Berkshire was built to outlast him, equipped with leaders across its operations capable of growing the company. Usually lavish in his praise of Jain, Buffett used his annual letter to shareholders in February to point out that his top lieutenant does not do it alone.

“Ajit’s achievements since joining Berkshire have been supported by a large cast of hugely-talented insurance executives in our various P/C [property-casualty] operations,” he wrote. “Their names and faces are unknown to most of the press and the public. Berkshire’s line-up of managers, however, is to P/C insurance what Cooperstown’s honorees are to baseball.”

But with Berkshire shareholders heading to Omaha for the group’s annual meeting on Saturday, it is Jain who, alongside Buffett and Abel, will offer a familiar presence on stage in the absence of Munger.

As Buffett wrote to investors in 2010: “If Charlie, I and Ajit are ever in a sinking boat — and you can only save one of us — swim to Ajit.”

This article is part of a series looking at the future of Berkshire Hathaway when Warren Buffett is no longer in charge. The first piece examined the record of the men set to run Berkshire’s $354bn stock portfolio. The next part will explore the challenge of managing Berkshire’s energy empire in the age of climate change