Two black Rolls-Royces pull up and the suited Easdale brothers, Sandy and James, leave their security detail behind to head into Glasgow’s smartest hotel. Picture them then, if you will, as teenagers, elbow deep in filthy work at their father’s scrap metal yard cutting, cleaning and separating cables and you’ll see how far they’ve come.

Hard graft has inched them every mile to join Scotland’s billionaires – the pair are now worth a joint £1.425 billion, up by £62 million in last year’s Sunday Times Rich List. Since they left school at 16, without qualifications (and Sandy is dyslexic), they’ve driven hard bargains to build a portfolio across multiple sectors from hospitality and property to transport, manufacturing and metal.

And unlike the split sibling partnerships of the Barclay and Issa brothers, Sandy, 55, and 52-year-old James are tighter than ever.

I had been told they fill a doorframe and indeed they cut intimidating figures at over 6ft, with strong hair and gimlet gaze. That is until they begin to talk: quick fire, a thread of Glaswegian humour tying them together as they finish one another’s sentences.

‘James has got a better smile than me,’ says Sandy to the photographer as they pose in the grand salon. Sandy wears the lace-up brogues, the sensible older brother perhaps, while James, the younger, with the ready smile, wears loafers.

The Easdale Brothers , Sandy (left) and James Easdale (right). The pair are now worth a joint £1.425 billion

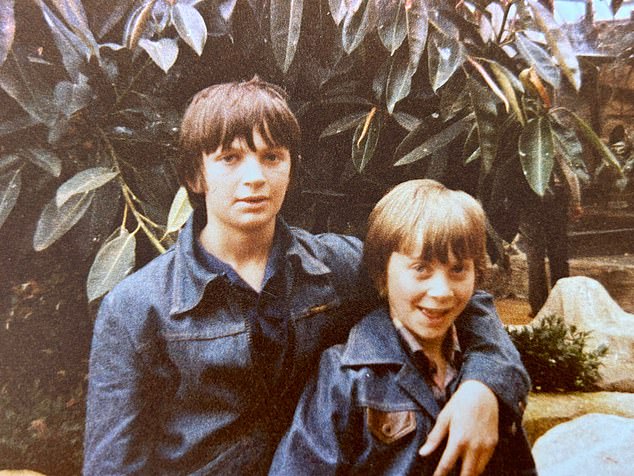

The two brothers as children. They left school at 16, without qualifications and have driven hard bargains to build a portfolio across multiple sectors from hospitality and property to transport, manufacturing and metal

Sandy said of his brother ‘Ah, we’re best friends and brothers. We turn to each other for comfort or advice. We’re often mistaken for twins. We’re both Aries, we clash horns but are grounded – if you believe that stuff.’ Pictured with Colin McMenamin (centre)

When they move to the chess board James quips: ‘We’d be kicking each other under the table if this was real.’

Are they the last billionaire brothers still talking? They laugh at the suggestion and give one another a bear hug.

‘Ah, we’re best friends and brothers,’ says Sandy. ‘We turn to each other for comfort or advice. We’re often mistaken for twins. We’re both Aries, we clash horns but are grounded – if you believe that stuff. I had to stop reading it as I was looking at it to shape my week!’

Clyde Metals, in Greenock, where it all began is still owned by the Easdales. Jim, their father, died aged 84 last month, unexpectedly. ‘We stayed by his bedside five days straight – and all without a drink,’ says Sandy, shaking his head.

Their father was a grafter, a good businessman but risk averse. Sandy holds out a wedding photograph of his parents on his mobile phone – a handsome couple. They credit their mother, Christina, who died ten years ago, as the driving force behind their insatiable desire to succeed.

‘She came from a bit of money and she was an inspiration to us in business. She’d always say, ‘Do it, you might not get the opportunity again.’ She bought an old sugar factory near us and split it into 12 separate industrial units. It was innovative in its day and we still earn money from it 40 years on.

‘Mum saw me buy my first Phantom Rolls-Royce at 38 which was pleasing for her,’ adds Sandy.

Even as gangly teenagers, the pair shared a small bedroom with a toy box between two beds. It was a simple enough childhood with the present of a Chopper each (red and blue) a highlight.

In 2004, they set their sights on McGill’s buses, which was then a small local transport company. The brothers have now transformed it into the largest independent bus operator in the UK and the McGill’s group turnover is now more than £120 million. Sandy (left) and James (right)

Sandy Easdale during the Scottish Championship Opening League Match between Rangers and Hearts, at Ibrox Stadium on August 10, 2014

Their teenage years were motivated, both worked hard and saved hard, with James buying a taxi while still at school and owning seven by the time he left. By their early 20s they had invested in six taxi firms running nearly 800 vehicles.

In 2004, they set their sights on McGill’s buses, which was then a small local transport company. The brothers have now transformed it into the largest independent bus operator in the UK and the McGill’s group turnover is now more than £120 million.

The brothers spent ten years in food and beverage – buying local pubs in Greenock which are now leased out. They invested in factories, commercial sites and office buildings where revenue could be more easily realised.

‘That’s why we love property – we may pay too much at the time, but you’ve got to weather the day -to-day and it may take years to come back – but it will come back. I can see why housebuilders are in difficulty – it takes five or six years for a project to complete – it’s nothing like that in commercial property.’

James Easdale during the Scottish Championship Opening League Match between Rangers and Hearts, at Ibrox Stadium on August 10, 2014. James bought a taxi while still at school and owned seven by the time he left

Consistent wins in familiar, some might say parochial, territory has been key to the Easdale success. One such example is Blairs windows and Sandy points out the huge Georgian wooden sash window made by the firm behind us in the bar at the Kimpton hotel, which would have cost £50,000 to make.

Other ongoing projects include £800 million of property developments including a 130-acre site in Glenrothes and a 70-acre project at the former IBM site in Greenock. ‘A really good business takes 25 years to flourish and we have to keep investing,’ says Sandy.

‘We’re deal-makers and we learn more through real-life, face-to-face deals. We love the chase day-to-day but as we age our attention span gets shorter – that’s why we’ve got good management teams.

They preside over a 3,000-strong staff with offices in London and Glasgow. ‘We don’t surround ourselves with endlessly excessive due diligence. We could get entangled with legal teams which would cost so much money. We just decide to go out and smash it.

‘Last week, we had two deals that fell flat on Thursday. Suddenly they’re live again on Friday. That would never have happened if lawyers had been involved.

‘We rely on this,’ says Sandy raising his mobile, ‘and old-fashioned networking.’

If they are workaholics, James insists they are relaxed ones, who won’t ever retire ‘and like to have a bit of banter’.

They’ve been known to kick up their heels in Mayfair, can’t bear ‘Dom’ (Dom Perignon) and their tipple of choice is ‘Rui’ (Ruinart champagne).

Sandy’s strength and stay is Gail, who he met a year after school and to whom he’s been married for 31 years and has two children in their 20s, Alexander and Gillian.

For James, it’s Lesley-Anne – his partner with whom he has James Jr, and Katherine. The families live 20 minutes from one another and the wives often raise a glass together.

‘James and I are in London Tuesday through Thursday – only tourists are in London on Friday,’ says Sandy.

‘We don’t know what each day will bring. Have brother will travel,’ adds James.

‘We fly commercial with BA to Heathrow a couple of times a week and always turn left. But we’re not Mariah Carey, we don’t want a private jet. Ask anyone who keeps one and you’ll find they’re kept on the tarmac for most of the time – a waste of money.’

It’s the simple maths that has also stopped the brothers investing in holiday homes abroad.

‘I don’t want to feel compelled to go to the same place year after year,’ says James. ‘It would be just like work trying to look after it. We’d rather go to a luxury resort where if the temperature of the pool isn’t right, it’s not my problem,’ he says.

‘It’s the same with boats – we’d rather rent them and dump them. To keep them in top condition is a waste of money.’

So do they have a weak spot, a passion where money is no object?

‘We can’t go in garages,’ replies Sandy deadpan. ‘I went in with my friend while he got his Porsche serviced and I came out with a new one.’

When I ask how many they have, James closes one eye as they reel off a list which doesn’t sound definitive: ‘We’ve got four Rollers on order, Ferrari, Lamborghini, countless Range Rovers and Bentleys.’

Little wonder James applied for (and won) planning permission for a £1 million extension to his Edwardian home in Kilmacolm.

What do they think of pensions?

‘You’re better off with property – location is key – and buying a house in a city such as Edinburgh, Glasgow’s West End or London and watching that grow – you’ve easily got £100,000 growth over ten years.’

At the mention of snobbery in the upper echelons of financial circles their hands fly up, animated.

‘It takes a long time to crack City banks. There’s an old-boy, old-school network in the City,’ says James emphatically. ‘We may not have been born with silver spoons in our mouths but we know how to use one. There are countless social barriers when you become successful but money still talks.’

Besides choosing to never work with ‘boring people’, their antennae are atuned to any hangers-on sniffing out money.

‘We pull the shutters down easily. We’re always on the attack and we’re so close we can tell if someone is clumsily trying to cosy up to us,’ says Sandy.

‘I can read his every blink, his every facial expression,’ adds James. ‘I can tell from a tilt of his head if a meeting isn’t going well’.

Is there anything they miss now they’re super rich?

Sandy doesn’t miss a beat. ‘Anonymity. We lost that when we got involved in football and attention on us exploded.’

The brothers bought a stake in Rangers Football Club in 2013 when the club was facing financial difficulties but left in 2015.

‘We went into Rangers with a passion, a love for the club and an open mind.

‘If we knew then what we know now it would be different.’

Adversaries are never far off. Their eyes flick to the door throughout our meeting and it’s clear from bank notes passed to Chuck the concierge that allies are appreciated.

If there is a family legacy it may come through Sandy’s son Alexander who has given up his career as a professional footballer and who, like his father, is learning the trade starting at the bottom in metal recycling.

‘Even now young guys come up to us in the pub and want to know how to make money. They want that one big idea. How dull to just want that one-off thing that nets you millions. For us it was never one big idea, it was about hard graft. It would be good if kids could learn that lesson.’

Some links in this article may be affiliate links. If you click on them we may earn a small commission. That helps us fund This Is Money, and keep it free to use. We do not write articles to promote products. We do not allow any commercial relationship to affect our editorial independence.