When hedge fund billionaire Ken Griffin told an industry conference this week that the US bond market was due some discipline, he was voicing the concerns of many investors about the impact of the government’s huge spending and debt issuance plans.

US government spending “is out of control”, he told the Futures Industry Association’s gathering in Florida. “And unfortunately, when the sovereign market starts to put the hammer down in terms of discipline, that can be pretty brutal.”

But while there may be good reasons for so-called bond vigilantes — hedge funds and other traders that punish free-spending nations by betting against their debt or simply refusing to buy it — to turn their attention to the Treasury market, analysts say they have so far failed to materialise.

After a brief flare-up of vigilantism in autumn last year, bond investors have redoubled their focus on the primary driver of fixed income markets: the path of interest rates. While the supply of new Treasuries has been big, so has demand, as investors in the US and beyond try to lock in relatively high yields ahead of an anticipated cycle of interest rate cuts.

“The whole fear over supply and bond vigilantes is a load of rubbish,” said Bob Michele, chief investment officer and head of the global fixed income, currency & commodities group at JPMorgan Asset Management. “I’m not seeing any evidence of it whatsoever.”

“For the last six months at least, clients have been coming to us asking ‘Where do I get into the bond market? When do I get into the bond market.’ Everyone has money to put into bonds,” Michele added.

The yield on the 10-year Treasury has fallen from a peak of 5 per cent in October to 4.3 per cent, reflecting higher bond prices. Inflows into US bond funds in the first week of March reached the highest level since 2021, according to EPFR data.

The heyday of shadowy market vigilantes fighting to rein in government deficits was in the 1990s during Bill Clinton’s presidency, when concerns about the federal budget deficit drove the 10-year yield from 5.2 per cent in October 1993 to 8.1 per cent in November 1994. The government responded with efforts to reduce the deficit.

But betting against bond markets became an increasingly dangerous game in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, as central banks including the Federal Reserve bought up vast quantities of their own government debt in a bid to drive down borrowing costs and stimulate their economies.

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, large Fed purchases thwarted the vigilantes, despite the US’s record borrowing needs.

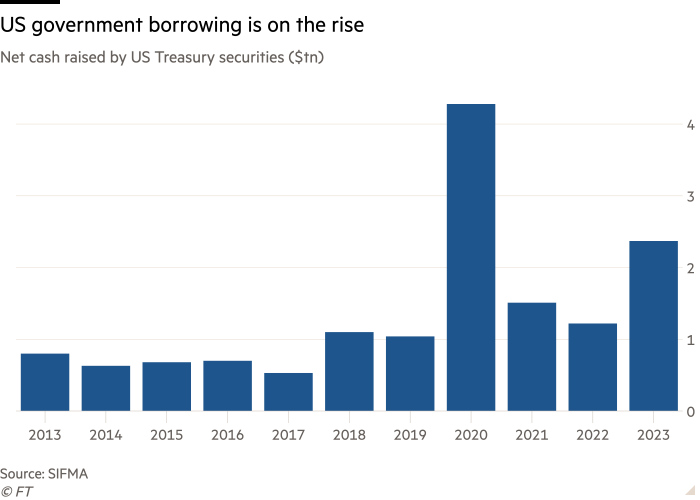

But as the Fed turned from buyer to seller, the quantity of US Treasury sales remained high, suggesting that conditions might finally be turning in the vigilantes’ favour. The quantity of Treasuries outstanding is set to rise by $1.7tn this year, according to Goldman Sachs. While this is lower than last year’s increase, it will be more weighted to longer-dated bonds, which are riskier for investors and harder for markets to digest.

Last autumn, Treasury yields hit a 16-year high. While that was driven by the Fed’s “higher for longer” message on rates, some investors said it was exacerbated by the sheer weight of issuance, after the US Treasury said in August it would increase the size of its debt auctions.

The episode had echoes of the bond market revolt in the UK a year earlier, when investors baulked at then-Prime Minister Liz Truss’s unfunded tax cuts, sending gilts into freefall.

The bond vigilantes were back, declared Edward Yardeni, the researcher who coined the term phrase in 1983. Kevin Zhao, head of global sovereign and currency at UBS Asset Management, in an October interview on CNBC similarly said that markets were acting to restrain runaway borrowing.

But yields then fell sharply, as markets shifted from fears over a prolonged period of elevated borrowing costs to frenzied speculation over when and how fast the Fed will cut them — reaffirming monetary policy’s primacy as the driver of bond market action.

“There was a shortlived protest by the bond vigilantes,” Yardeni said in an interview this week. “But they went back into siesta mode. Siesta doesn’t mean they are gone forever. The supply issue is still out there, but the bond market doesn’t seem to care much about it.”

Some analysts say the abundance of cash parked in money market funds, which invest in ultra-short term government debt, acts as a potential source of continued demand for Treasuries. Money market assets in the US reached a record high of $6.1tn this week, according to ICI data. Some of that “dry powder” was likely to find its way into longer-dated debt once investors grew sufficiently convinced that the Fed was set to lower rates, said Michele.

But, for some investors, the threat of vigilantism remains. Vincent Mortier, chief investment officer at Europe’s largest fund manager, Amundi, said Treasuries are at risk of a major sell-off if a victory for Donald Trump in November’s US presidential election is accompanied by concerns over the level of government spending similar to those that triggered the 2022 gilts crisis.

In addition, if stubbornly high inflation means the Fed is unable to lower rates as quickly as the market expects, investors could once again turn their attention to the enormous wave of Treasury supply to come, according to Torsten Sløk, chief economist at Apollo Global Management.

The Treasury department has held record-sized auctions for two- and five-year notes this month, which will grow again in April and May. Would-be bond vigilantes were “still dozing”, said Sløk. “But a really weak auction could wake [them] up.”

Additional reporting by Jennifer Hughes in Boca Raton, Florida