It’s one of Britain’s best-preserved Bronze Age settlements, lending it comparisons with Italy’s Pompeii.

Now, a new study gives greater insight than ever before into the lives of Brits at Must Farm in Peterborough 3,000 years ago.

The inhabitants lived a life of ‘cozy domesticity’ and dined on honey-glazed venison and meaty porridge, archeologists at the University of Cambridge say.

Other surprisingly sophisticated features of the settlement include jewelry with imported beads, clothes of fine flax linen, and even a recycling bin for tools.

Must Farm was less than a year old when it was mysteriously destroyed by a catastrophic fire, although it’s thought all the inhabitants escaped.

Thousands of artefacts found at Must Farm have been studied for the new report. This bowl was found with remains of porridge still inside, which was mixed with animal fats (possibly goat or red deer), along with a broken spoon (left)

The new study is from Cambridge Archaeological Unit (CAU), which excavated Must Farm nearly a decade ago.

It details thousands of artefacts there, including a pottery bowl with the fingermarks of its maker captured in the clay was found still holding its final meal.

Chemical analysis revealed traces of a wheat porridge mixed with animal fats – possibly goat or red deer.

Incredibly, a broken wooden spatula used for stirring was still resting against the inside of the bowl.

‘The site is providing us with hints of recipes for Bronze Age breakfasts and roast dinners,’ said project archaeologist Dr Chris Wakefield at CAU.

‘Chemical analyses of the bowls and jars showed traces of honey along with ruminant meats such as deer, suggesting these ingredients were combined to create a form of prehistoric honey-glazed venison.

‘It appears the occupants saved their meat juices to use as toppings for porridge.’

Must Farm inhabitants likely had favourite cuts of meat, often only bringing the forelegs of a boar back for roasting, for example.

Preferred fish dishes would have included pike and bream, which could have been caught from a slow-moving river below.

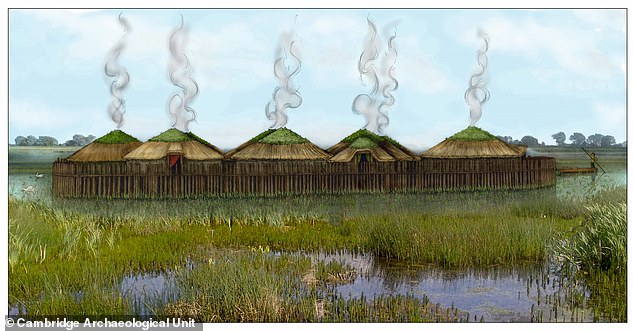

Archaeologists think Must Farm consisted of large wooden roundhouses that were constructed on stilts above the river.

The entire settlement would have stood approximately 6.5 feet (2 metres) above the riverbed, with walkways bridging some of the main houses.

It would have been relatively small, holding up to 60 people including children.

An illustrated reconstruction of the Bronze Age stilt settlement in its heyday. It would have been less than a year old when it was destroyed by a catastrophic fire

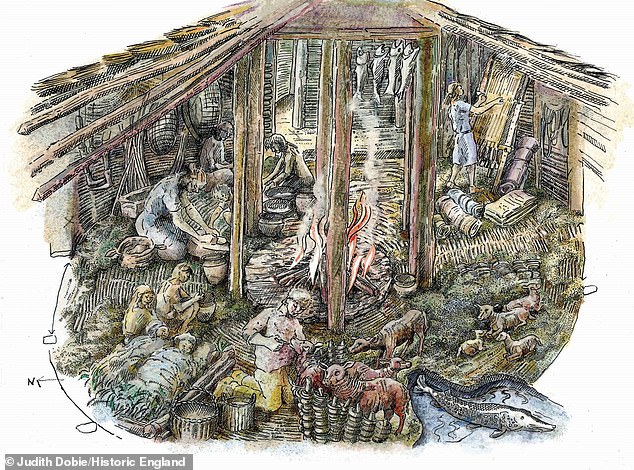

Illustration of ‘cozy’ domestic life inside one of the roundhouses at Must Farm almost 3,000 years ago

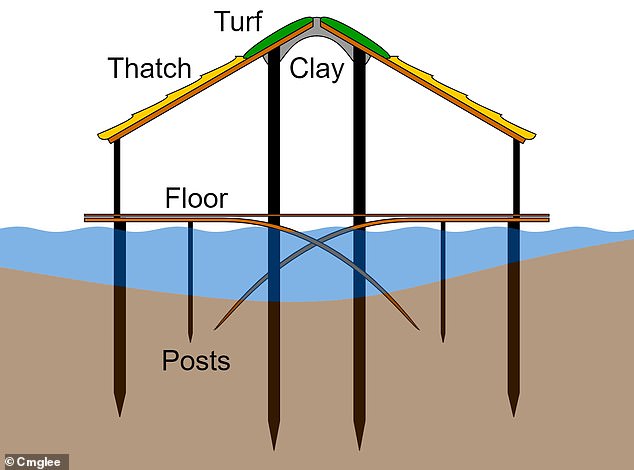

Simplified cross-section of a typical house at Must Farm. Each roundhouse roof had three layers – insulating straw topped by turf and completed with clay, making them warm and waterproof but still well ventilated

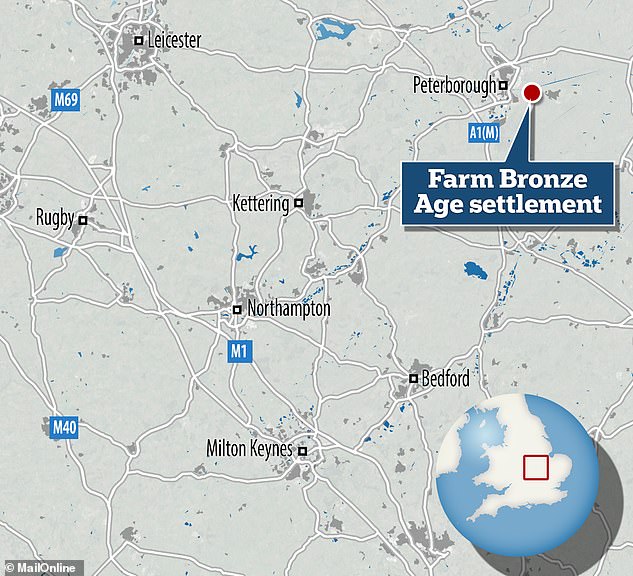

Must Farm Bronze Age settlement – described as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’ – is located just east of Peterborough in Cambridgeshire, England

An intact hafted axe that had been placed in the silt directly beneath one of the roundhouses, perhaps a token of good fortune, or an offering to some kind of spirit on completion of the build

Ceramic and wooden containers, including tiny cups, bowls, and large storage jars, were found

Must Farm was discovered in 1999, but it wasn’t until 2015 that CAU began a dig at the site.

Since then nearly 100 scientists and specialists have been analysing the finds from the ancient English settlement.

They include swathes of tools, ornaments and personal possessions, including a necklace of beads made from glass, amber, siltstone and shale, imported from as far away as Denmark and Iran.

In all, 49 glass beads were found and experts think they all came from far-flung places, including Northern and Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

‘Such items would gradually make their way across thousands of miles in a long series of small trades,’ said Dr Wakefield.

Cloth fragments, loom weights and bobbins – little cylinders wound with thread – show inhabitants made their own clothes at the site.

Ceramic and wooden containers that could have been used in food preparation and serving include tiny cups, bowls and large storage jars.

Spears found on site, up to 11 feet in length, as well as swords, were as likely to be used in animal hunts as on rival groups.

There were also sickles (crop-harvesting blades), axes and curved ‘gouges’ used to hack and chisel wood, as well as hand-held razors for cutting hair.

One intact axe was found directly beneath one of the roundhouses, which the experts think was deliberately placed there as a token of good fortune, or an offering to some kind of spirit on completion of the build.

Meanwhile, a large wooden recycling bin contained damaged bronze tools that were probably waiting to be smelted down and refashioned.

Remains of a necklace with beads necklace of beads made from glass, amber, siltstone and shale, imported from as far away as Denmark and Iran

People at Must Farm likely lived a life of ‘cozy domesticity’ before it was engulfed by fire. Pictured, fragment of textile

Pictured, fragmented pots likely used in food preparation, designed to stack inside one another to save space

Full findings from the Must Farm site – excavated by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit (CAU) in 2015-16 after its discovery on the edge of Whittlesey near Peterborough – are published in two reports

A member of the Cambridge Archaeological Unit uncovering an axe head during excavations at the Must Farm site in 2016

Some mysteries still remain surrounding Must Farm, including the cause of the fire that destroyed it which ‘will probably never be known’.

‘Some argue it may have come under attack, as the occupants never returned for their goods, which would have been fairly easy to retrieve from the shallow waters,’ said David Gibson at CAU.

As the fire broke, buildings and their contents would have collapsed into the muddy river below, which ‘cushioned’ the scorched remains.

The combination of charring and waterlogging led to ‘exceptional’ preservation, lending the site the nickname ‘Britain’s Pompeii’.

There was no evidence of humans dying in the fire, but several young sheep were trapped and burnt alive, as indicated by skeletal remains.

Several small dog skulls suggest the animals were kept domestically, perhaps as pets but also to help catch prey.

Dog ‘coprolites’ – fossilised faeces – reveal the pets fed on scraps from their owners’ meals.

The new study is published in two volumes (part I and part II), both available online.