In The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Vroomfondel and Majikthise — representatives of Amalgamated Union of Philosophers, Sages, Luminaries and Other Thinking Persons — attempt to shut down supercomputer Deep Thought before it threatens their livelihoods by providing some certainty in answering the ultimate question of Life, the Universe and Everything. Financial analysts face no such threat.

Doubt and uncertainty have never been in short supply in the finance world. And efforts to quantify important theoretical variables have done nothing to dent the livelihoods of its professionals.

The most famous example is probably the ‘equity risk premium’, or ERP — the amount of excess return investors supposedly demand to invest in stocks over and above the risk-free rate to compensate for additional investment risks. If the ERP is high, it’s a good time to buy stocks. If it’s skimpy or even negative it’s time to run for the hills, or at least for the fixed income market. So controlling what is understood to be the ERP is a big deal.

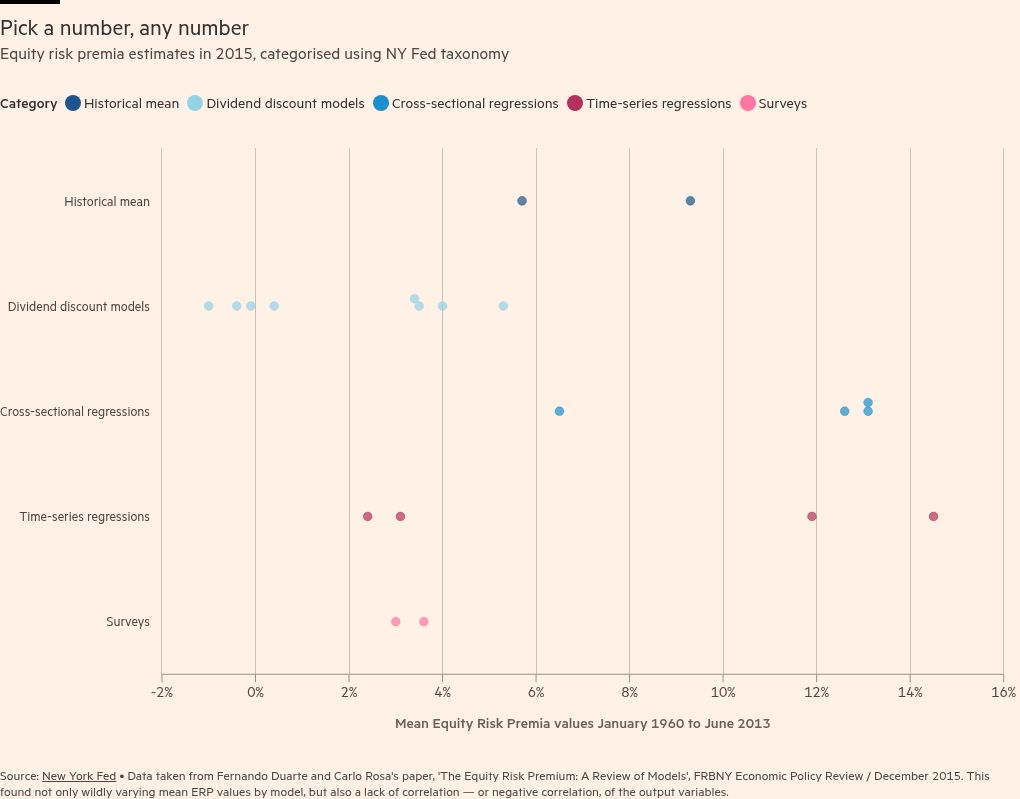

There are a myriad of attempts at modelling the ERP, each spitting out values that not only differ from each other, but can also move in opposite directions over time. The point was made elegantly a decade ago in this NY Fed paper, which looked at twenty different ERP models — the outputs of which are shown in the chart below:

This hasn’t stopped investors, public intellectuals, or columnists from continuing to refer to the ERP in public as some kind of single observable metric, even if their private understanding is far more nuanced.

But the example we really want to talk about is bond ‘term premia’ — already the subject of two, or maybe even three, FTAV posts this year.

As the NY Fed explains:

In standard economic theory, yields on Treasury securities are composed of two components: expectations of the future path of short-term Treasury yields and the Treasury term premium. The term premium is defined as the compensation that investors require for bearing the risk that interest rates may change over the life of the bond.

You can see why central bankers might be interested in term premia. They consider bond markets to be conduits for the transmission of monetary policy and look to them to understand how expectations are forming around their future policy actions. From time to time they even inflate their balance sheets to the moon in an effort to reduce term premia. So having some idea of what term premia might be will be useful to them.

But — and here’s the rub — there’s an almost complete consensus that term premia are not directly observable. They need to be estimated.

So for years, bond-types could step into this seemingly protected and rigid area of doubt and uncertainty to posit wildly different views about what the bond market was *really* saying. And if policy-types wanted to understand the bond market they would need access to their very own bond whisperer, perhaps one who shared their political priors.

Then came the models.

While econometric term premia models have roots least back into the 1980s, the three most famous models today come from economists working for the US Federal Reserve system.

Don Kim and Jonathan Wright, working for the Federal Reserve Board’s Division of Monetary Affairs, published what has come to be known as the Kim-Wright model in 2005. Three years later New York Fed economists Tobias Adrian, Richard Crump, and Emanuel Moench published what became known as the ACM model. And in 2012, San Francisco Fed economists Jens Christensen and Glenn Rudebusch came up with their own version — the so-called CR model.

To do this they each estimate, in slightly different ways, the level of *true* investor expectations as to where short-dated interest rates will be in the future. As the chart below shows, their estimates for average expectations around short-term interest rates ten years’ hence have been sometimes lower and sometimes higher than US Treasury yields.

Subtracting this estimated true expectation of average short-term interest rates from the appropriately termed US Treasury bond yield in the next chart makes this all a bit clearer. When the models reckon true expectations for short rates are lower than US Treasury yields, term premia are high and (if the models are to be believed) inventors are being paid to take duration risk. And when the models reckon that true expectations for average short rates are higher than US Treasury yields, this means that term premia are negative, and that investors (who believe the models) are paying for the privilege of taking duration risk.

Because the models themselves are complex, almost continually cited by central bankers, and (importantly) have outputs that are easy to download and chart, they quickly achieved a kind of intellectual hegemony. But did these efforts solve the term premia question?

Matt Klein wrote an FTAV post almost a decade ago about how the numbers coming out of the ACM model can be swung by a cool hundred basis points if you make reasonable tweaks to sample start dates and assumed holding periods. The Fed replied to Matt’s post with a blog of their own, largely agreeing.

In other words, while models didn’t provide an answer to Life the Universe and Everything, they do provide an answer to the question of where average expectations for short term interest rates could credibly be thought to be, and from this answer an answer to where term premia were. It’s just that these answers can be jimmied around by changing the underlying assumptions.

Any model, like any person, will always be sensitive to its inputs.

But let’s go back to the raison d’être of these models. They seek to construct theoretical estimates of term premia because term premia are *unobservable*.

Really?

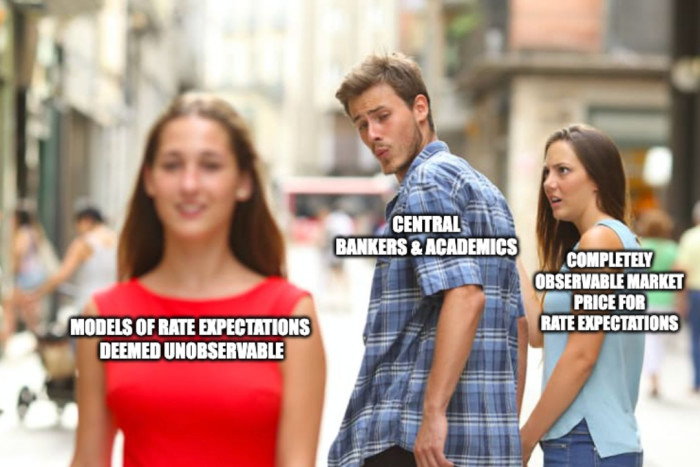

There is a directly observable market price for the expected average short term rate over a given period. It’s called the fixed leg of an Overnight Index Swap, or OIS. Or to put this in meme form:

This is not some pokey little market either. Last year there was over $260 trillion of traded volume referencing USD OIS, a further €163.5 trillion referencing Euro OIS, and over £75 trillion referencing SONIA. In other words, there is a lot of skin in this game.

The difference in yield between government bonds and the fixed leg of an OIS looks uncannily like the dictionary definition of the term premium. It was this yield spread that we used in our own decomposition of US and UK bond yield changes into changes to expected real rates, inflation expectations and term premia at the start of the year.

How do UST–OIS asset swap values measure up against the numbers that theoretical models of term premia produce? For one thing, they seem much less volatile. And the market price has the advantage over the econometric estimations of being anchored by vast numbers of traders competing with almost unimaginable sums in a high-stakes competition to be least wrong.

What do bond-types reckon? Barclays’ rates market doyen Moyeen Islam told us that OIS-spreads “offer something more concrete to market practitioners” than the output of theoretical models, though he didn’t write these off.

We got in touch with Tobias Adrian — author not only of probably more than half the coolest shadow-banking papers we’ve ever read, but also the ‘A’ in the most widely-used ACM model. He agreed that OIS may be preferable to term premia models in practice in measuring near-term policy rate expectations. But he also reckons the further you go out the curve, the more OIS becomes muddied with liquidity and counterparty risk. As such, he told us:

OIS markets are helpful in gauging investor expectations of monetary policy expectations over short horizons. But expectations backed out from term premium models have better forecast performance over medium to long-term tenors, especially in being able to account for premia.

In other words, frictions in the markets that produce OIS rates mean that OIS rates will be subject to the same unobservable positive and negative term premia that econometric models seek to quantify.

We can see that this might be true, but can’t see how the claim would be easily falsified.

Term premia models are complicated frameworks built by brilliant minds seeking to infer the unobservable. It is easy to get lost in their methodology and be awed by the outputs. Financial markets by contrast are calculation engines that produce very simple observable results. Channelling Douglas Adams one last time (in this post, at least), “I’d take the awe of understanding over the awe of ignorance any day.”

Further reading:

— What’s a “term premium”? (FTAV)