It was around dawn on a chilly day last November when West Virginia state troopers forcibly extricated Jerome Wagner out from a 25ft-deep pit where he was locked to a drilling machine being used to finish construction of a beleaguered gas pipeline.

The veteran climate activist was trying to draw attention to the Mountain Valley pipeline (MVP) – a 300-mile (480km) fossil fuel project mired by environmental controversies and blocked by court orders and regulatory red tape until it was pushed through by the Biden administration in mid-2023.

Biden resurrected the MVP to secure the vote of fossil fuel-friendly West Virginia senator Joe Manchin, which was needed to pass a debt ceiling bill. The decision came amid worsening climate disasters across the US, and was condemned by environmentalists for overriding due process and widespread local and scientific opposition to the pipeline.

The move triggered a wave of peaceful protests and civil disobedience against the pipeline in Virginia and West Virginia. It wasn’t the first time residents and climate activists had tried to thwart construction of the MVP, but this time the crackdown was unprecedented.

Almost 50 non-violent activists were arrested in multiple counties across both states, with charges ranging from trespass and obstruction to conspiracy and abduction, which carry maximum prison sentences of up to 10 years.

The actions ranged from rallies and brief walk-ons of MVP land to roadblocks and activists chaining themselves to machinery to disrupt the final stages of construction through some of the most environmentally sensitive forested Appalachian mountains and waterways.

“Legal intimidation is a tactic that’s designed to scare folks and incapacitate the movement,” one pipeline resistance organizer said.

For his action at the MVP site, Wagner, a retired engineer and committed Catholic, was charged with four misdemeanors – trespass, two counts of obstructing an officer and one charge under West Virginia’s controversial new Critical Infrastructure Protection Act, which significantly increased penalties for protests against oil and gas facilities.

“I don’t regret a single thing,” said Wagner, who has been arrested more than a dozen times during 15 years of climate activism. “Fossil fuels need to be stopped, period.”

Earlier this year, Wagner admitted to obstruction in a plea deal and was sentenced to 12 months in jail, with eight months suspended. The MVP is also suing Wagner for punitive damages.

“In retrospect it was a risky thing to do. I could still be sitting in jail, and the civil suit is very onerous. But as the climate gets worse and states double down on protecting fossil fuel profits, people will get even more desperate,” said Wagner, who remains on probation after serving 60 days’ jail time.

The crackdown against peaceful protests and civil disobedience is on the rise in the US – and globally – as people become increasingly desperate and frustrated at the failure of governments and corporations to prioritize the climate crisis, biodiversity and clean water over profits.

Civil disobedience is a form of political protest that involves breaking the law in a planned, symbolic way – which activists and rights experts say is part of the bedrock of a democratic society and in the tradition of civil rights movements. In New York, police made more than 700 arrests this summer, during a series of peaceful protests in front of the headquarters one of the world’s largest fossil fuel financiers, Citibank.

West Virginia is among 22 states to have approved laws that can punish people protesting against oil rigs, gas pipelines, dams and other so-called critical infrastructure with long prison terms and hefty fines.

It is the most recent state to charge climate activists under a critical infrastructure law, in what critics say is part of a growing crackdown on peaceful protests being pushed by a coalition of rightwing lawmakers and their corporate allies.

“The fossil fuel industry is running out of cards to play,” said Bill McKibben, founder of Third Act, a non-profit that organizes people over 60 years old to work on climate, democracy and racial justice. “Solar and wind are cheaper and cleaner, so brute force – and a lawsuit or criminal prosecution – is really about all they have left.”

In a state once dominated by coal barons, emails obtained by the Guardian show that oil and gas lobbyists coordinated behind the scenes with West Virginia officials, which included meetings, emails and penning a draft bill for the chief counsel to the state legislature’s powerful energy committee – just days before the critical infrastructure bill was introduced in early 2020.

It was passed a few weeks later despite opposition from residents concerned about environmental harms and the law’s impact on civil rights, and provided for a maximum five-year sentence and up to $15,000 in fines.

In an email to lawmakers, one resident said: “Our first amendment rights are sacred … These anti-protest bills are a direct assault on this right and we will not stand for it.”

A public relations firm, whose lobbyist represented two oil and gas trade groups, took credit for organizing support for the bill.

After the law was passed, local residents and campaigners continued to oppose the pipeline by petitioning the courts, regulators and lawmakers, and through direct action.

And by mid-2023, pipeline construction had been halted by the courts for almost two years, and the company was dealing with hundreds of clean water citations, canceled permits and growing opposition. The MVP was about $4bn over budget, with construction across the steepest mountain slopes and hundreds of streams, rivers and waterways unfinished.

In June 2023, Biden, the self-proclaimed climate president, caved to Manchin’s demands singling out the pipeline as being “required in the national interest”, and even added provisions shielding the MVP from further legal challenges. Manchin said he was “proud” to have secured approval via the debt ceiling legislation and that he was looking “forward to the day this important piece of energy infrastructure is up and running”.

The International Energy Agency has made clear that no new fossil fuel infrastructure can be built if the world is to have any hope of avoiding the most catastrophic global heating.

In the months after construction restarted, 48 people were arrested and at least 51 people and two alleged organizations have been sued in 13 separate lawsuits by MVP.

“The government has long been in the pockets of the fossil fuel industry in West Virginia, but we also have a long history of resistance to extractive industries, which helps explain the critical infrastructure bill,” said one activist, who was involved in the MVP protests. “But the idea that the Mountain Valley pipeline is ‘critical’ is absurd … These projects actually create a demand for fossil fuels and are here to make money not meet public need.”

Last year was the hottest year ever recorded, with devastating extreme heat, floods, drought and wildfires striking across the US – and countries across the planet. The MVP will emit an estimated 89m metric tons of planet-warming gases annually, the equivalent of 19m cars.

Wagner was among eight people, including six senior citizens, charged under the state’s critical infrastructure law.

In the most recent case, Rachel Berkrot was charged with three misdemeanors including trespass on a critical infrastructure facility, after chaining herself to an excavator on Peters mountain in the Jefferson national forest in April 2024 as the MVP project was drilling under the Appalachian trail. This was among the last construction sites, and where tree-sits prevented the MVP from clearing trees for 95 days in 2018.

Berkrot, an activist and educator, faces up to two years in jail. The case continues.

The first charges under the new law were tied to an action on 7 September 2023 at the Greenbrier River crossing in West Virginia, when six climate activists – including five grandmothers – were arrested and charged with a critical infrastructure misdemeanor, in addition to trespass and obstruction.

River crossings were targeted by activists as the MVP was being rushed to be constructed through waterways, having obtained the federal permits thanks to the debt ceiling bill override. Just weeks earlier, Manchin had celebrated the resurrection of the MVP at the Greenbrier River.

Four of the activists were sitting in rocking chairs with umbrellas that said “No MVP”, blocking an access road to the construction site – each with one foot immersed in a 55-gallon drum filled with cement. “A livable planet tomorrow depends on serious and dedicated action today to end fossil fuels,” said Jess Grim, one of the so-called Rocking Chair Rebellion members at the time.

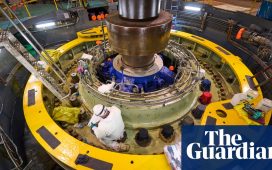

Meanwhile, Rose Abramoff and Martha Zinn, who were locked to a massive drill, were also charged with unlawful injury to or destruction of property. “The stakes are so high,” Abramoff, a climate scientist, said at the time. “We cannot build this pipeline and meet our climate goals.”

After months of uncertainty, the Greenbrier Six eventually pleaded guilty to simple trespass and each paid a $100 fine plus court costs; all other criminal charges were dropped in the deal.

But the ordeal continues: all six are being sued by the MVP on multiple counts, which include requests for injunctions that would prevent them from “obstructing in any way MVP’s ability to conduct its business” and from encouraging others to engage in civil disobedience or obstructing the MVP, according to court filings.

The company is seeking at least $45,629 in alleged damages “to MVP in salaries, wages, and other expenses incurred through delay of the project”, in addition to an unspecified amount of punitive damages – which under state law could be as much as half a million dollars.

Over the past 10 to 15 years, the fossil fuel industry has sued hundreds of activists, NGOs, scientists and journalists in the US, in what the legal advocacy group EarthRights International calls attempts to silence or harass critics, and are known as strategic lawsuits against public participation (Slapps).

“By design, these tactics are not just targeting individuals in isolation, but are trying to dismantle broader movements,” said Kirk Herbertson, senior policy adviser for EarthRights International, a non-profit that tracks legal action linked to fossil fuel companies.

“They’re threatening activists with financial ruin with Slapps and criminal fines instilled in some of these anti-protest laws, [as well as] trying to encourage more stringent, harsher penalties for civil disobedience to take this tactic off the table – because it has such a successful record of placing high levels of pressure on companies,” Herbertson said.

The MVP, a joint venture in which the gas giant EQT Corporation is now the majority shareholder and operator, is claiming millions of dollars in alleged damages resulting from peaceful and mostly brief acts of civil disobedience. Such lawsuits can chill free speech and debate, which are vital for a healthy democracy, according to the UN and other legal experts.

EQT did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In Virginia, one of the lawsuits includes 22 named individuals and 25 Jane Does, and here the MVP is claiming $4.35m in damages – without presenting details or evidence in the complaint of what specific damages were incurred from the work stoppages the company claims activists caused. “As a result of defendants’ actions, MVP has sustained irreparable harm,” the complaint states.

“The claim is absurd, meant to instill fear and intimidate people so they stop protesting. But fossil fuels are not in the best interests of the planet or the people,” said one of the activists being sued.

Efforts to pass new anti-protest laws have so far failed in Virginia, but MVP activists are facing numerous serious charges for peaceful blockades and other acts of civil disobedience.

In one case in Giles county, 10 activists are charged with multiple misdemeanors and two felonies: conspiracy to commit unauthorized use of a motor vehicle and abduction – of a machine operator prosecutors allege was scared to leave. The case is ongoing.

The recent crackdown against MVP activists is in addition to more than 100 arrests and 10 civil lawsuits in previous years of organized civil disobedience across both states.

The MVP is now operational. The so-called Slapps continue.

“The fact MVP is ratcheting up their scare tactics through escalating trumped-up criminal and civil charges shows that we are having an impact,” said another MVP activist, a retiree hit with criminal and civil charges after participating in their first act of peaceful civil disobedience.

“The MVP may be operational in spite of our efforts to resist, but we’ve made the path for future pipelines that much more difficult … [There is] an increasing number of individuals willing to put their bodies on the line to stop the madness,” she added.

Earlier this year, West Virginia lawmakers amended the state’s critical infrastructure law to broaden offences and punish some second-offence felonies with up to 10 years in prison.

Yet the new critical infrastructure legislation could have been even more severe.

Back in 2020, lawmakers and their fossil fuel allies tried to pass legislation that made any intent to willfully damage, destroy, vandalize, deface, tamper with equipment, or impede or inhibit operations a mandatory felony. This was changed thanks to intense lobbying by concerned West Virginia residents, and while the legislation is still very broad, a felony requires proof of at least $2,500 of damage.

“When we realized the bill was going to pass, we tried our best to minimize the harm and keep West Virginia residents with legitimate concerns about destructive energy projects from being swept up in this dangerously vague law that could put them in a cage for a very long time,” said Chad Cordell, a resident and environmental campaigner.

Fighting criminal and civil charges demands time and money, and it can prevent activists from participating in certain actions.

“From a seemingly endless stream of civil lawsuits to unfounded felony charges to a months-long misdemeanor jail sentence for a grandfather, MVP and the governments of Virginia and West Virginia are using their immense power and resources to deter and punish principled grassroots resistance to MVP’s reckless and exploitative pipeline project,” said Alex Marquardt, executive director of Climate Defense Project, a non-profit which represents social justice activists facing criminal and civil charges across the US.

“West Virginia’s Critical Infrastructure Protection Act is yet another example of the state prioritizing the interests of fossil fuel lobbyists over the people of Appalachia.”

EQT did not respond to a Guardian request to comment on the allegations. In a promotional video released in July, Toby Rice, EQT’s president and CEO, said: “MVP is going to create amazing opportunities for our communities, for our country, for our planet and for our allies, and that’s why we like to refer to it as America’s most valuable pipeline.

“Getting here has not been an easy road; over seven years and over $7bn … but thanks to the proud energy champions we have in our industry and in DC and across the country, we’ve been able to get MVP completed. While I hope it will get easier for us to get energy infrastructure built in the future … I hope what people understand is that these energy champions were not fighting for a pipeline, we were fighting for America.”