From the UK’s hottest day to the hottest year on record globally, there’s no doubt some worrying temperature records have been broken in recent years.

Many people think the rate of global warming has dramatically accelerated or ‘surged’ over the past 15 years – and is a cause of more extreme weather.

But a new study says there is not any statistical evidence for this so-called ‘surge’ or ‘leap’.

Researchers looked at long-term global surface temperatures since records began back in 1850 and found no evidence of a surge since the 1970s.

While the academics agree that human-caused global warming is happening, they say it is not statistically ‘surging’ as some claim.

Global warming is happening, but not statistically ‘surging,’ reveals the new study which was co-authored by a Lancaster University statistician (file photo)

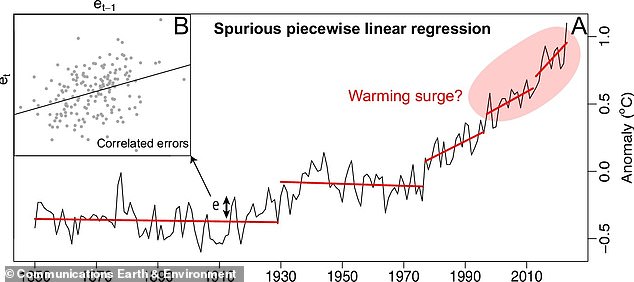

The team’s findings demonstrate a lack of statistical evidence for an increased warming rate that could be defined as a surge. In this graph, the circled part section is the part that some scientists have highlighted as a period of increased warming (the ‘surge’), but the team say this model is ‘not plausible’ (inset)

Recent years have seen record-breaking temperatures and heat waves globally, including the hottest UK record set in July 2022.

Last year was officially the hottest year since global records began in 1850, while that the 10 warmest years in the historical record have all occurred in the past decade (2014-2023).

However, the new study found a lack of statistical evidence for an increased warming rate that could be defined as a surge.

‘Our concern with the current discussion around the presence of a “surge” is that there was no rigorous statistical treatment or evidence,’ said co-author Professor Rebecca Killick, a statistician at Lancaster University.

‘We decided to address this head on, using all commonly used statistical approaches and comparing their results.’

Last year was officially the hottest year since global records began in 1850. Pictured, a man recoils as a fire burns into the village of Gennadi on the Greek Aegean island of Rhodes, July 25, 2023

Global mean surface temperature’ (GMST) is average temperature of Earth’s surface and is widely studied to monitor climate change. Pictured, GMST data from NOAA

The team say a ‘current debate centres around whether there has been a recent surge or acceleration in the warming rate’.

To learn more, Professor Killick and partners at UC Santa Cruz, Clemson University and University of Nebraska in the US studied ‘global mean surface temperature’ (GMST),

GMST is simply the average temperature of Earth’s surface – and a metric that is widely studied to monitor climate change.

It’s usually recorded by weather balloons, radars, ships and buoys, and satellites, over both oceans and land.

The experts looked at GMST from four main agencies that track the average temperature of Earth’s surface – NASA, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA), Berkeley and the UK’s HadCRUT – since 1850.

Although GMST is rising long-term, in the short-term it tends to fluctuate due to natural phenomena – like major volcanic eruptions and the El Niño Southern Oscillation.

Therefore, the team deemed a warming ‘surge’ as statistically detectable if it exceeded and sustained a level above those temporary fluctuations over a long period of time.

‘Imagine temperature records plotted on a graph – a small change in the slope would require more time to detect it as significant, whereas a large change would be evident quicker,’ said Professor Killick.

After accounting for short-term fluctuations in the GMST, a warming surge could ‘not be reliably detected’ anytime after 1970, the team found.

‘No change in the warming rate beyond the 1970s is detected despite the breaking record temperatures observed in 2023,’ they write in their paper, published in Nature Communications Earth & Environment.

The team stress that a surge in global warming may be happening – just that it’s not detectable yet.

‘Of course, it is still possible that an acceleration in global warming is occurring,’ said lead author Claudie Beaulieu, a professor of ocean sciences at UC Santa Cruz.

‘But we found that the magnitude of the acceleration is either statistically too small, or there isn’t enough data yet to robustly detect it.’

Recent years have seen record-breaking temperatures and heat waves globally, including the hottest UK record set in July 2022. Pictured, London’s Primrose Hill on July 10, 2022 during a heatwave

In 2022, UK temperatures broke the 104°F (40°C) mark for the first time, hitting a new record of 104.5°F (40.3°C) on July 19 at Coningsby in Lincolnshire

Professor Beaulieu agreed that Earth is the warmest it has ever been since records began because of human activities.

She said: ‘To be clear, our analysis demonstrates the ongoing warming; however, if there’s an acceleration in global warming, we can’t statistically detect it yet.’

In response to the findings, Richard Allan, a professor of climate science at the University of Reading, suggested that only one line of evidence was considered for the study.

‘In fact, when all lines of evidence are scrutinized it is apparent that climate change is accelerating rather continuing steadily,’ said Professor Allan, who was not part of the research team.

‘Halting global warming by stabilizing Earth’s climate and limiting further damage from worsening extreme weather and rising sea levels is only possible through rapid and massive cuts in greenhouse gas emissions.’

Dr Kevin Collins, a senior lecturer in environment and systems at Open University, said there is a ‘very real danger’ that the findings are misinterpreted.

‘With many people and places experiencing year on year record temperatures around the globe in the last decade, it is very human to assume global warming is accelerating or “surging”,’ said Dr Collins, also not involved with the study.

‘However, through an authoritative statistical analysis of temperature increases since 1970, this research concludes that there is no detectable surge – yet.

‘Instead, the results suggest global warming is occurring at a steady state.

‘However, as the authors acknowledge, this may be because the size of any acceleration is either statistically too small, or there is simply not enough data to detect a surge in the last decade.’

‘In other words, it is still too early to tell if the last decade – the warmest on record – represents a “leap” in the warming trend.

‘By 2035 or 2040 we may look back and be able to see from 2015 onwards there has been a fundamental shift in the warming trend.’