Prime Minister Rishi Sunak managed last year to get the electricity grid around his North Yorkshire home reinforced to help heat his private outdoor swimming pool.

While the 43-year-old picked up the tab himself, the task gave him an indication of one of the biggest projects facing the UK: upgrading the nation’s electricity system in the transition to net zero.

The government estimates £170bn-£210bn must be invested by 2050 on expanding and reinforcing the onshore cables and pylons that carry electricity to people’s homes and businesses from the country’s power stations.

The upgrades are needed so the networks can cope with the planned switch from fossil fuels to clean electricity, which will see households using battery cars and heat pumps reliant on electricity generated by wind and solar farms.

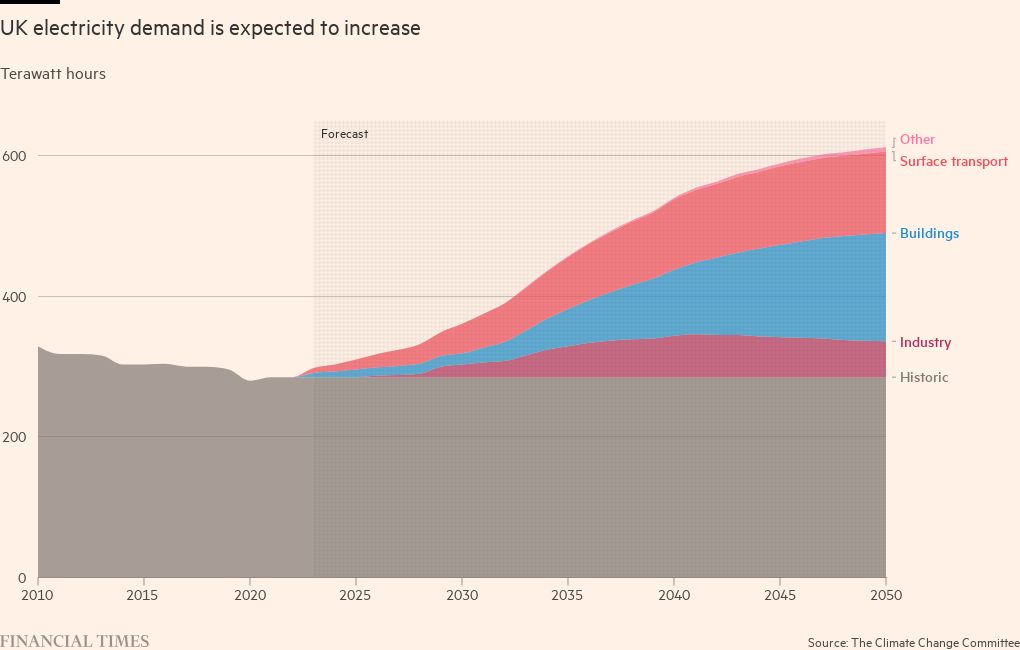

The UK government’s Climate Change Committee forecasts electricity demand could double by 2050, the target date for net zero carbon emissions.

But the large investments required, more than the £150bn the Energy Networks Association estimates has been spent since privatisation of the system in 1990, underline the challenge for the companies that own and run those networks.

The FTSE 100 companies National Grid and SSE, and Scottish Power, controlled by Iberdrola, own the main transmission networks and some of the regional distribution networks they feed into, which take electricity on to households.

The other regional distribution networks are UK Power Networks, part owned by billionaire tycoon Li Ka-shing’s CK Infrastructure Holdings; Northern Powergrid, owned by Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Energy; and Electricity North West, owned by a consortium led by Kansai Electric Power.

Regulators face the balancing act of trying to keep investors happy for the financing necessary to upgrade and maintain them while at the same time ensuring energy bills are affordable.

“The challenge is striking a balance between incentivising investment with rates of return that reflect company risk and performance, while ensuring that consumers do not pay more than is necessary to make future networks fit for purpose,” said Julia Prescot, deputy chair of the National Infrastructure Commission, which has been asked by the government to prepare a report on making the regional networks ready for net zero.

The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero said it was “driving forward the biggest reforms to our electricity grid since the 1950s” and had “announced measures to transform our grid network — bringing forward £90bn of investment over the next 10 years”.

The balance between bills and investment has already proved a problem for energy regulator Ofgem, which was criticised in 2020 by the National Audit Office, the UK spending watchdog, for allowing owners to make too high returns.

Think-tank Common Wealth said the distribution networks paid out £3.6bn to their owners between 2017 and 2021. UK Power Networks, with about 8mn consumers in London and south-east England, has paid out £434mn over the past two years for a total of £2.4bn in dividends since 2010.

North-east network Northern Powergrid, which serves an estimated 4mn homes and businesses, paid Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway Energy £200mn in dividends in 2023 for a total of £351.5mn since 2004.

The sector’s appeal to investors has been underlined by merger and acquisition activity over the past few years.

National Grid paid £7.8bn in 2021 to buy Western Power Distribution, a regional group, from US company PPL.

The deal was followed in 2022 by the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan paying £1.5bn for a 25 per cent stake in the transmission lines owned by SSE in Scotland.

Both price tags were well above the companies’ regulated asset value.

Yet, despite return concerns, Ofgem is mindful that money is needed to finance network upgrades and pay for repairs and maintenance as the economy moves to clean power.

This means making sure they are attractive to investors for equity fundraising.

As a result, Ofgem is considering assessing companies’ “investability” in the next set of price controls for the transmission networks — National Grid in England and Wales and Scottish Power and SSE in Scotland — to determine acceptable levels of returns to ensure bills do not soar.

The plans for the “investability” metric follows lobbying from the sector, which has warned about “unprecedented demand for new equity financing” in the shift to net zero, according to Ofgem consultation papers.

The regulator added that its price controls are “designed to ensure that networks have access to the funding they need to deliver energy at least cost to consumers and meet net zero targets”.

However critics, such as Citizens Advice, fear Ofgem’s plans could contribute to unfairly high bills for consumers.

“We don’t really understand why you would need to introduce an additional criteria of ‘investability’,” said Andy Manning, principal economic regulation specialist at Citizens Advice.

Customers have been hit with record high energy payments over the past few years, with costs for electricity and gas networks partly responsible as they account for about 20 per cent of the typical household bill.

“We feel the tone [from Ofgem] is there are concerns that these [networks] won’t be attractive enough [to investors] — but we have yet to see any evidence of this,” Manning added.

High levels of debt are also a concern for some, with the potential for credit rating downgrades that could affect a company’s ability to raise money for investment.

Ofgem is looking at whether any further financial resilience measures are needed for the regional distribution companies, such as strengthening reporting requirements on debt structures.

Lawrence Slade, chief executive of the Energy Networks Association that represents the network owners, stressed the importance of attracting investment in the run-up to net zero.

Policy and regulation “need[s] to be bold in order to support the government’s ambitious goals while providing the stability and clarity required to efficiently secure the level of investment needed”, he said.

Manning warned that setting returns too low might fail to attract investment, but setting them too high risks damaging public confidence in the shift to a green economy.

“It’s not a one-way argument. Without public confidence, net zero won’t be delivered,” he added.

Additional reporting by Gill Plimmer

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here