In 1973 and 1979 war in Israel and turmoil in Iran twice ruptured the oil market, triggering an inflationary surge that sapped western economies and unseated a US president.

In the decades since, the possibility that new strife in the Middle East could deliver another administration-ending jump in oil and petrol prices has hung like a spectre over the White House.

Last week, the fears suddenly looked overblown.

On Monday, less than a week after the first-ever direct military strikes by Iran on Israel brought fears of a wider regional war, oil prices settled at $87 per barrel — flat versus their level just before a strike on the Iranian consulate in Damascus precipitated the eruption.

It was a notable non-reaction from oil markets, especially given the threat Iran poses to the Strait of Hormuz, the sea lane through which passes one in every five barrels of petroleum consumed globally each day. Demonstrating its menace to the waterway, Iran seized a vessel there on April 13, the same day it launched its attack on Israel.

The crude price calm in the face of this turmoil owes much to events 7,000 miles away in the shale fields of North Dakota and west Texas, where drillers have left global markets awash with American oil.

“Shale has redrawn the map of world oil in a way most people don’t seem to understand,” said Daniel Yergin, vice-chair of S&P Global and a Pulitzer Prize-winning energy historian. “It has changed not only the supply-demand balance but it has changed the geopolitical balance and the psychological balance.”

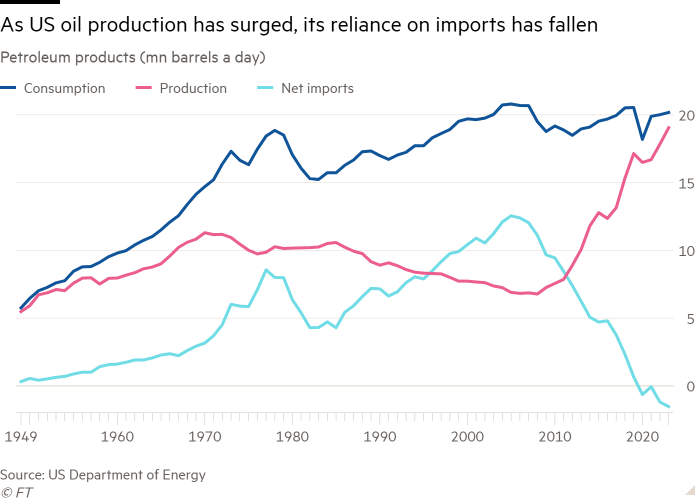

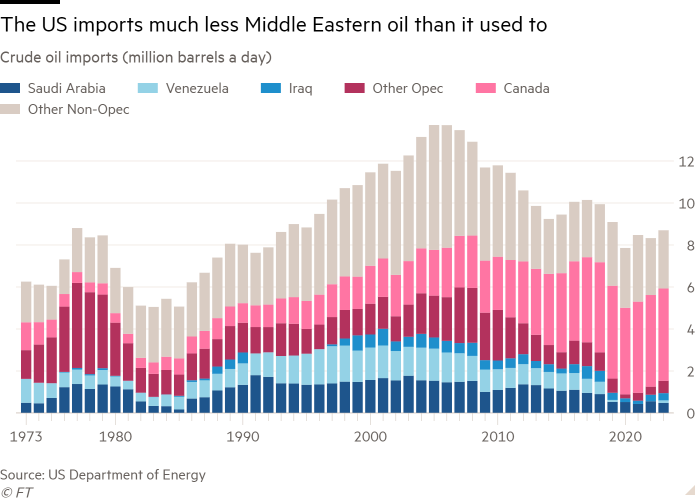

The numbers are stark. Two decades ago the US produced about 7mn barrels a day of petroleum and consumed 21mn. Gulf countries like Saudi Arabia and Kuwait — which send oil through the Strait of Hormuz — were among the US’s most important foreign suppliers.

Now the US produces almost 20mn b/d of petroleum, roughly on par with consumption. Imports from the Gulf have plummeted, and the US became a net oil exporter for the first time in 2019. The prolific Permian Basin shale of Texas and New Mexico pumps more oil than Kuwait, Iraq or the UAE, three of Opec’s powerhouses.

The strategic advantages are profound, say analysts, even for a White House eager to transition away from fossil fuels to clean energy.

The shale surge has blunted the impact of supply cuts made by Opec in the past two years, they say, and allowed President Joe Biden’s administration’s to impose sanctions on suppliers such as Venezuela and Russia, while tightening restrictions on Iran — all without fear of driving up oil prices.

“It is a huge turnaround from where we were at in the 1970s,” said Harold Hamm, chair of Continental Resources and a shale pioneer. “If you didn’t have the shale revolution now you would have $150 oil . . . You would be in a very volatile situation. It would be horrendous.”

Rising shale supplies also helped keep the lights on in Europe following Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, with shipments of US liquefied natural gas — previously labelled “molecules of US freedom” by the Trump administration — helping to wean the continent off Russian piped supplies.

The extent of shale’s significance to oil markets was already visible in 2019, Yergin said, after a devastating drone attack on the Abqaiq crude processing facility in Saudi Arabia, the nerve centre of its oil sector. Crude prices rose sharply — and then fell back almost as quickly.

“I think that’s when it became clear to me that there had been a great rebalancing,” Yergin said.

Even so, experts warn that the US still remains vulnerable to oil shocks. All- out war between Israel and Iran, or a big new plunge in exports — for example if the Strait of Hormuz were to be shut — would inevitably remove supplies from a fungible global market, raising petrol prices from Beijing to Boston.

“We are still acutely exposed to geopolitics and market manipulation. And shale doesn’t really help with that,” said Jim Krane at Rice University’s Baker Institute. “Yes, we’re a big producer. But more importantly, we’re a big consumer, and that’s where our exposure lies.”

The US accounts for about 20 per cent of global demand, driven by the country’s reliance on big, gas-guzzling vehicles.

Shale also remains uniquely vulnerable to price gyrations, making it an unreliable component of the global oil market, say some analysts.

It was only four years ago that crashing oil prices during the Covid-19 pandemic pushed many shale producers to the brink of bankruptcy. Then- President Donald Trump was forced to plead with Saudi Arabia and Russia to slash their own output to prop up prices to spare the shale patch — a demonstration of US energy vulnerability.

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggered an oil price increase in 2022, it was Biden’s turn to press the Saudis for help, this time urging them to pump more to beat back soaring US petrol costs.

Shale executives are themselves sceptical that drillers could raise supply quickly enough to rescue the global economy from a sudden oil shock. Wall Street remains reluctant to fund new drilling campaigns by producers that earned a reputation for profligacy in recent years.

The Biden administration has been conscious of that dynamic — and also of the political consequences of higher gasoline prices ahead of elections. Last year, one senior Biden adviser said Wall Street was being “un-American” in holding back drillers.

The White House’s diplomatic focus has been to prevent further turmoil in the Middle East.

“We have an election and the Biden administration cannot, cannot, cannot afford to act recklessly or precipitously in the region. They’re being extraordinarily careful with every step they take,” said Matt Gertken, a geopolitical strategist at BCA Research.

The administration has also said it remains willing to use stored strategic reserves of oil to keep prices at bay. At about $3.68 per gallon, US petrol prices may be lower than in other economies — but they are up 15 per cent this year.

“Bottom line is that it is always better as a nation to have your own oil,” said Amy Myers Jaffe, a professor at NYU.

“But alas, [crude] prices will go up if there is a market supply shock and that will probably transmit itself back to US drivers as higher fuel prices — global market and all that.”