Europe will enter its second winter since turning off the taps to Russia’s gas pipelines with record-breaking reserves. By the end of summer, gas storage facilities were 90% full, two months ahead of schedule. But observers warn that the energy crisis is not over yet: Europe may have dramatically cut its reliance on Russian gas, but it has never been more exposed to price shocks in the global market.

For more than a decade, Russian gas pipelines were Europe’s biggest single source of imported gas. In the wake of the Ukraine invasion, these imports plunged by two-thirds from their peak in 2019. In their place Norway’s pipelines became Europe’s largest single source of gas.

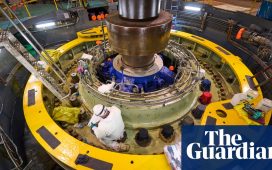

The US has also benefited from Europe’s energy upheaval. Imports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from the US stood at nearly 64bn cubic metres last year, up from zero in 2015. LNG is gas that has been cooled to -160C, a process that turns it into a liquid that can be transported by ship.

European governments expect the seaborne gas to keep coming. Currently, Spain, the UK and France have the highest number of terminals for processing imported LNG, collectively making up 60% of the continent’s capacity. But, according to S&P Global’s Atlas of Energy Transition, other European countries are planning to develop new capacity as they look for alternatives to Russian gas.

This plan is far from foolproof. Last month, a violent market surge of more than 40% in a single day was triggered by news of strike action by workers at a gas project in Australia. It’s rare for Australia to supply gas to Europe, but experts warned that the shock of less gas in the global market could still reverberate in the northern hemisphere.

This is a stark reminder that the best way to guard against rising gas prices is to use less gas.

UK

British households will be hoping for a mild winter this year, especially since the government pulled the plug on its energy bill support scheme well before a planned boost to homegrown energy can be expected to kick in.

In the past, the UK has imported just 2% of its considerable gas consumption from Russia. Instead, it relies on pipeline imports from Norway and deliveries of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to its vast import terminals from suppliers around the world. Last year, the UK imported a record 25.6bn cubic metres of LNG, representing almost 45% of total gas demand.

In late September, the gas transmission operator, National Gas, said it was “unlikely” that gas supplies would be at risk this winter unless “a very cold winter … should coincide with a major interruption to one of our gas supply sources”. But the risk of this happening should not be discounted, the operator said.

The UK is still expected to remain exposed to the impact of soaring international gas prices. The country’s gas storage facilities are among the smallest in Europe relative to gas consumption. In the wake of the Ukraine invasion, the UK government supported the reopening of the Rough gas storage facility in the North Sea, which was retired in 2017. Its owner, Centrica, brought 20% of the facility’s previous capacity back into use, and this alone added about 50% to the amount of gas the UK can store.

Unlike other European countries, the UK has made little coordinated effort to reduce gas consumption at a national level. Ministers vowed to tackle the energy crisis by helping with household energy bills in the short term while in the longer term encouraging investment in homegrown energy sources.

Winter energy payments worth £400 per household – some of the most generous support payments in Europe, introduced by Rishi Sunak when he was chancellor – have been replaced with schemes to help the most vulnerable. Critics fear that the government is relying on mild weather and ample availability of LNG in the global market to weather another winter.

Germany

Before the Kremlin’s war, Germany sourced as much as half of its gas by pipeline from Russia, for generating electricity and heating homes. Soon after the invasion, Europe’s largest economy quickly set out a crisis plan to slash its reliance on Russian fuel.

The plan included laws requiring the country’s vast gas storage facilities – the largest in Europe – to be 65% full by August, 80% full by October, and 90% full by November.

Germany differed from other EU nations in its insistence on energy efficiency measures, designed to cut reliance on gas for good. It set a target to reduce gas use by 20%, supported by a string of policy measures. These included mandatory heating system maintenance and upgrades for landlords and owners of large buildings. Companies with high energy use were obliged to implement small efficiency measures with a payback period of less than three years. These appeared to have paid off: Germany used almost 15% less natural gas last year, helped by a relatively mild winter.

While the Berlin government was working to reduce demand for gas, it was also importing it. Germany has increased its gas pipeline imports from the Netherlands and Norway, and developed three new LNG import terminals. The country’s gas buyers are looking to sign LNG import contracts with suppliers in the US, Qatar, and UAE. Germany hopes to bring another three floating LNG import terminals online by January 2024.

The new import terminals, hastily developed under Germany’s energy acceleration law, passed in May 2022, have met with resistance by some local groups and environmental campaigners. They argue that Germany may be reducing its reliance on Russia, but it is locking in its dependence on fossil fuels.

France

France sourced just 17% of its gas from Russia before the war, making it far less dependent on the Kremlin than some of its European neighbours. France, with its fleet of nuclear power plants, is also far less reliant on gas: it uses it for about 16% of its energy needs compared with 25% in Germany and more than 40% in the UK.

French reliance on Russian gas may be low, but the sanctions blocking Russian imports took effect last year against a backdrop of serious problems with its nuclear plants, raising fears that France may face winter blackouts.

In response, the French government put in place measures to reduce the country’s energy use by 10% compared with 2019 by next year, and by 40% by 2030. These included a campaign encouraging households and businesses to turn on the heating two weeks later than usual, and only when indoor temperatures fall below 19C. It also offered civil servants €2.88 (£2.50) a day to work from home.

The government also has plans to increase gas storage levels and install a new LNG import terminal at Le Havre in Normandy.

Spain

Spain is not as dependent on Russian energy supplies as some EU nations thanks to a string of gas import terminals. Nevertheless, it has taken steps to guarantee its winter energy supplies, and managed to reduce gas demand by 21% between August 2022 and March this year.

These included mandatory energy-saving measures such as limiting heating in public buildings to no higher than 19C, and air conditioning to no lower than 27C. Shop and restaurant doors were ordered to be kept closed to conserve energy, and lights in shop windows had to be switched off after 10pm.

To help Spanish households with energy bills, the government cut VAT on gas from 21% to 5% last year. In addition, the EU approved an €8.4bn Spanish and Portuguese plan to reduce wholesale electricity prices in the Iberian market by capping the price of gas used to produce electricity. Operating as a direct grant to electricity producers, it was intended to save households 15% to 20% on their energy bills.

Thanks to its energy infrastructure, Spain is able to export electricity to its neighbours: over summer 2022, those exports covered 30% of demand in Portugal and 4.5% in France. Gas exports rose by 55% over the first three months of 2023, thanks to ships carrying LNG and the extension of a gas pipeline to France.

A plant capable of loading 100 ships a year with LNG for transport across Europe has also been opened in the north-western port of Gijón.

Poland

In April last year, when the Kremlin began demanding payment in roubles, Poland and Bulgaria were the first EU countries to be cut off from Russian gas. At the time, almost half of Poland’s gas came through the Yamal pipeline from Siberia. But unlike Germany, which relies on gas to generate about 15% of its electricity, Poland generates most of its power from coal; gas is used in industry and home heating.

For years, the biggest economy in central and eastern Europe has been trying to reduce its reliance on Russian gas. Since the invasion of Ukraine, Poland has accelerated its pursuit of imports via LNG terminals. Earlier this year, state-owned oil and gas company Orlen finalised a 20-year deal with Sempra of the US to import 1m tonnes of LNG a year.

Warsaw is working to increase the country’s LNG import capacity. Within months, it hopes to have increased the capacity of its Świnoujście LNG terminal from its current 6.2bn cubic metres a year to 8.3bn cubic metres.

Poland’s LNG imports are already on the rise. A total of 58 vessels unloaded LNG there in 2022, according to commodities information provider Icis – a sizeable increase on the 35 vessels recorded in 2020 and 2021. This year, the terminal is expected to accept a record 60 vessels, according to Icis.