Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Evergrande’s homepage is frozen in time at just over a year ago. Back then its founder, Hui Ka Yan, still seemed hopeful he could save the world’s most indebted developer. “All Evergrande employees must . . . never give up,” the charismatic tycoon tells executives in one video, exhorting them to finish thousands of apartments left incomplete after the company officially defaulted on its $300bn debt in 2021.

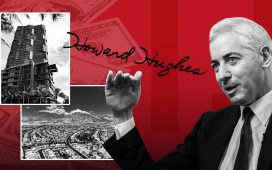

But the brave words could not avert disaster. This week a Hong Kong judge declared “enough is enough”. Evergrande, whose collapse helped spark a property crisis that has spurred a slowdown in the world’s second-largest economy, should be liquidated. Hui was not able to react. The entrepreneur, named Xu Jiayin in Mandarin, disappeared in September and is being held somewhere in China on suspicion of involvement in “illegal crimes”.

But the ruling and his detention are an ignominious end to the rise of a former steelworker who became one of China’s highest-rollers during the boom years. In less than three decades, Hui created one of the country’s largest property companies while dabbling in football, electric vehicles and theme parks. He used his fabulous wealth to ingratiate himself with elites from Beijing’s “red aristocracy” to the British royal family.

“Of all the developers, I have to say he was one of the more aggressive ones,” says Desmond Shum, author of Red Roulette, a book about elite Chinese business and politics, who knew Hui in his heyday. “So when the market turns, that these people are the first ones to go on the chopping block, it’s not surprising.”

Like many of his generation, Hui’s personal life mirrored China’s rapid changes after opening its economy in the late 1970s. Born into poverty in Henan province, he was raised by his grandmother. After working in the steel industry in the 1980s, he launched Evergrande in 1996 just in time to catch a housing boom driven by China’s new middle class.

After expanding into 280 cities, according to Evergrande’s website, Hui invested in theme parks and poured funds into a government “shantytown” redevelopment programme. This left him heavily exposed to China’s smaller cities, where experts warned the market was heading into oversupply.

He and other developers often sold houses before construction, using the funds to acquire land while banks offered mortgages on the unbuilt properties. Developers and local governments became addicted to the debt-fuelled model. “That is the problem with a bubble. Once you’re in, you’re in — it’s almost impossible to get out,” said Zhu Ning, professor at the Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance and author of China’s Guaranteed Bubble.

Hui came to embody a brash new breed of Chinese tycoons, sporting a gold Hermès belt buckle, buying mansions in Sydney, Hong Kong and London, and flying around in private jets. In 2015, he bought a 60-metre mega yacht and celebrated the victory of his football team, Guangzhou Evergrande, in Asia’s Champions League, with co-owner internet billionaire Jack Ma and Britain’s Prince Andrew. In 2017, he topped the Forbes China rich list, with a total net worth of nearly $43bn.

Those who knew him say he had an easy-going, bright personality, perfect for high-level networking. According to one banker: “Hui is a person with high EQ . . . [otherwise] how was he able to persuade some big Hong Kong financiers to invest in him and Evergrande?”

Hui’s downfall began in 2020 when President Xi Jinping’s government introduced a new policy limiting leverage as it sought to redress economic imbalances. Evergrande’s aggressive model meant that this translated quickly into a liquidity crisis. Its offshore bond restructuring was in effect blocked last year after the authorities found irregularities in its mainland arm, leading to the liquidation.

Few expect, however, that the liquidation order will extend to the mainland. Beijing would not surrender control of the potentially politically explosive process of resolving Evergrande and other developers’ debts — and finishing their vast number of incomplete apartments, analysts said.

Hui was not available for comment and Evergrande did not immediately respond.

Many now believe Hui could follow other tycoons who have fallen foul of Beijing, such as Xiao Jianhua, a politically connected financier who was snatched from the Four Seasons in Hong Kong by Chinese agents in 2017 and sentenced to 13 years in jail. “Even if someone wanted to contact him [Hui], they might not be able to do so,” Hong Kong tycoon Joseph Lau, who used to play cards with him, told reporters in November.

His fall marks the “ending of an era”, says Shum. “Many Chinese business people over the last few decades were maximum risk-takers because the economy was on a one-way upward trend . . . So when the downturn comes during the Xi era, people are completely unprepared for it.”

Hui’s legacy promises to be mixed at best. On Beijing’s outskirts, Central Mansion is a former Evergrande housing project “rescued” by the state-owned China Railway Construction. After a long idle period, six of its 15 buildings were finished this month, an agent said, while the rest are set for the end of 2024.

One customer tells the Financial Times she is concerned about her investment after the liquidation — the compound will still be managed by an affiliate of Evergrande Property Services. But the realtor reassures the FT that “there’s nothing to be worried about” — Evergrande no longer has any real influence. “After all boss Xu is still behind bars,” he says.

With additional reporting by Cheng Leng in Hong Kong, Ryan McMorrow in Beijing and Sun Yu in New York