Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt is clearly keen to cut taxes in next week’s UK Budget. But money is tight. One strategy would be to go ahead, pay for it by squeezing future public services spending and then leave a Labour government to clean up the mess. An alternative, very different strategy would be to do what Treasury insiders have been trailing and announce “smart” tax cuts. What does that mean?

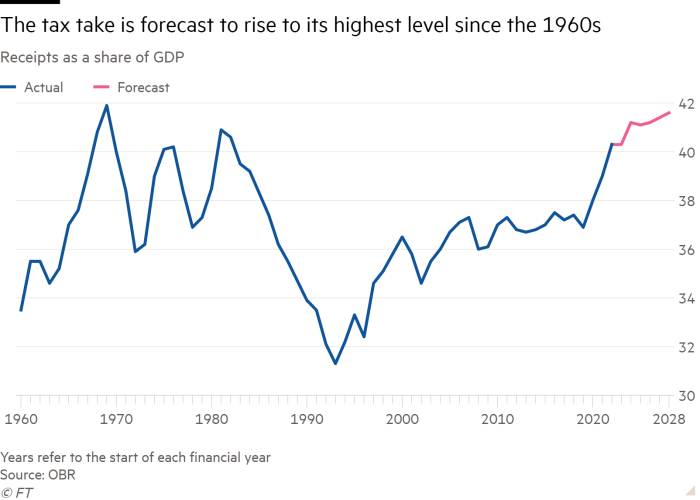

Smart could mean anything voters will reward. But, awkwardly, Britons don’t seem to be in the mood. A poll for YouGov found that only one in four respondents favoured prioritising tax cuts over funding public services. That is despite the fact that, over the next couple of years, receipts as a share of gross domestic product will grow to their highest level since the 1960s as frozen thresholds drag people into higher tax brackets.

Perhaps it would be wiser to define smart in relative terms. Relative to lifting income tax thresholds, a cut to the basic rate is not pro-poor. But relative to scrapping the top 45p rate it makes Hunt look almost saintly. A real-terms cut to fuel duty might seem strange given the small matter of climate change. But compared with a special tax cut on coal, it has the air of genius.

If such sleights of hand seem unsatisfying, there are always lurking economists ready with their own definitions of “smart”. Perhaps lowering the overall tax cut could be clever if the economy crashes, the Bank of England hits the lower bound of interest rates and the government needs something to encourage people to spend. (We’re not there yet.)

Smarter could mean simpler, though examples were probably easier to find in the past, before the government dropped the special taxes of the 18th and 19th centuries on clocks, gloves and dogs. Dan Neidle of Tax Policy Associates suggests that old-style stamp duty, a tax on housing transactions, should get the chop. It is relevant for a tiny number of contracts, but has a huge economic cost as lawyers rake in hefty fees confirming it doesn’t apply.

Alternatively, smart could mean something that minimises the distortions associated with the existing system, and encourages things such as investment or work. If people respond enthusiastically enough, a lower tax rate could even raise revenue.

Tax cuts that pay for themselves are like the unicorns Conservative MPs dream of — tricky to spot in real life. One briefing note from the Institute for Fiscal Studies published in 2017 did suggest that the revenue-maximising effective income tax was somewhere between 53 per cent and 87 per cent, and probably higher than the top rate England, Wales and Northern Ireland have now.

That said, there are some gremlins lurking in the tax schedule, which have crept in as governments have tried to claw back certain benefits from higher earners. The loss of child-related benefits imposes a marginal tax rate of more than 70 per cent for those earning around £50,000, and of over 100 per cent for those earning around £100,000.

No one’s heart should bleed for people who are earning well above Britain’s average, of course. But everyone’s brain should hurt at the idea that working more could leave you with less take-home pay.

Even if a tax cut doesn’t raise revenue, it could have welcome effects. There is a growing literature showing how research and development responds to tax incentives. Cutting stamp duty land tax would increase people’s freedom to move home.

Making such tax cuts even smarter would mean coupling them with tax increases elsewhere. The political economy of tax reform is hard, and a tax cut in isolation would probably represent a missed opportunity. “We should be thinking much more about the system,” says Helen Miller of the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Ditching stupidly high marginal tax rates for some parents could come alongside higher average rates. Stamp duty could be cut in favour of higher capital gains tax on property or reformed council tax. The list of investments businesses can use to lower their corporation tax bill could be broadened, but alongside something to reduce the built-in bias towards debt financing.

All this might sound rather ambitious for a government in its last gasps. A final option would be to take the smart route as suggested by history. A study of OECD countries published in 2017 suggested that tax cuts aren’t actually particularly likely in election years. A glance at Britain’s experience of the past 20 years suggests that pre-election giveaways aren’t very common. Maybe, just maybe, the smartest option is no tax cut at all.