This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. Carl Icahn bought the dip in JetBlue. The airline’s stock, which has had a dismal run lately, was up nearly 20 per cent yesterday after the investor announced a big stake. This is the very same Carl Icahn who lost $9bn shorting the market. Stockpicking is hard; short selling is harder. Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

Is Arm really an AI stock?

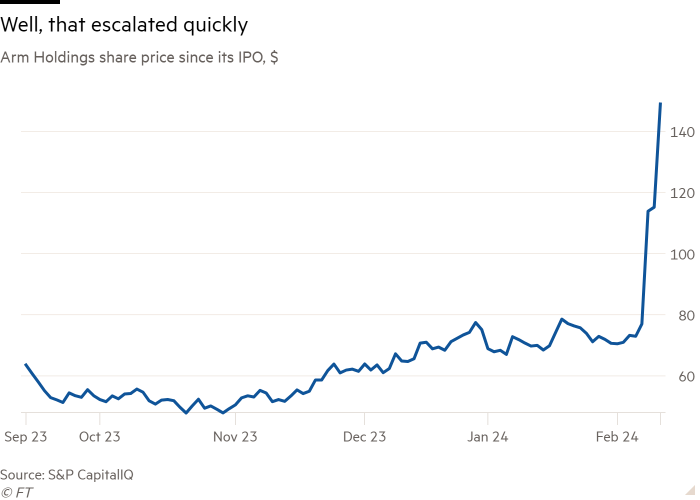

It’s been a big week for the chip designer Arm Holdings. Since the company’s earnings call last Wednesday, the stock has just about doubled:

There are two basic explanations of this mad leap. One is that Arm, which is 90 per cent owned by SoftBank, has a small free float, and a chunk of the shares that trade might have been sold short prior to the strong earnings report. Earnings estimates for the next fiscal year have risen about 11 per cent since the report, which is significant, but a slightly odd fit with a doubling of the stock.

The second is that Arm is now a fully-paid-up AI story stock. The Financial Times, for example, reported that the results were “boosted by strong demand for artificial intelligence”. The company itself is not doing much to discourage the AI hype. The quarterly shareholders’ letter said “Arm’s licensing revenue was supported by increasing demand for new technology driven by all things AI . . . AI on Arm is everywhere”, and noted the company’s designs feature in Nvidia and Google AI products.

The key characteristic of Arm’s chip designs is they use less energy per unit of performance than rivals’, which helped them become the industry standard for mobile processors, where their market share is 100 per cent. Power efficiency has also helped the company take significant share in data centre chips, where energy use is an increasingly important constraint. But Arm is a CPU (central processing unit) company. AI computing is driven primarily by GPUs (graphics processing units), which are particularly good at doing lots of things at once, which is what AI work requires. So the Arm-AI hype struck me as slightly off.

I put this somewhat under-informed intuition to Dylan Patel, chief analyst at SemiAnalysis, a specialist research house serving both the chip industry and Wall Street. “I don’t see the AI story here,” he said, “but I do think there is a data centre story.” The distinction is important. AI requires a huge amount of computer power, and while the core AI jobs will be done by GPUs, there are lots of ancillary computing tasks to be done: “serving web pages, gathering data, formatting it for AI”.

Gene Munster, a partner at the technology investor Deepwater Asset Management, concurred. Arm “is part of the AI story. If you look at the [overall computing] infrastructure, there is going to be so much change, it will be a rising tide, data centres are going to be rebuilt, and they will be part of that.” Among AI stocks, however, Arm is “on the list, but near the bottom”, with Nvidia, AMD and Taiwan Semiconductor near the top (Deepwater does not have a position in Arm).

Everything in computing is now branded as AI, just as a few years ago everything was cloud, and a few years before that everything was mobile. But the returns from the move to mobile or the cloud were not evenly distributed. The returns from the move to AI will be uneven, too. Some stocks will be lifted by the tide; some will be at the crest of the wave.

That does not mean Arm has little growth potential. Patel says the company has a huge amount of room to increase the royalty rates it charges device makers that use its chip designs. He notes Arm charges phonemakers something on the order of 50 cents a phone for its mobile CPU designs. Qualcomm’s royalties for using its radio chips in a high-end phone might run something like $13. Closing that gap is a growth story that does not require chanting “AI, AI, AI”.

Are dividends really back?

Meta’s recent dividend announcement, small though it was, helped push the company’s shares up 20 per cent. More broadly, too, it stirred investors’ imaginations. The social media group’s move “intensified” client interest in the outlook for dividends, report equity strategists at Goldman Sachs. “The dividend is back,” trumpeted The Economist.

If the dividend were indeed back, that would be a big deal. Reinvested dividends compound dramatically. Since 1926, an investor who held the S&P 500 would have gotten 38 per cent of her returns from dividends, with the rest coming from price returns. Between 2013-22, however, that number slipped to 17 per cent, according to Bank of America, as more flexible share buybacks became the favoured way to return cash to shareholders.

Meta is still doing boatloads of buybacks, but the marginal shift towards dividends strengthens the case that higher bond yields are nudging companies to “routinely place a predictable layer of dividends on their stocks to keep investors sweet”, the FT’s Katie Martin wrote last week.

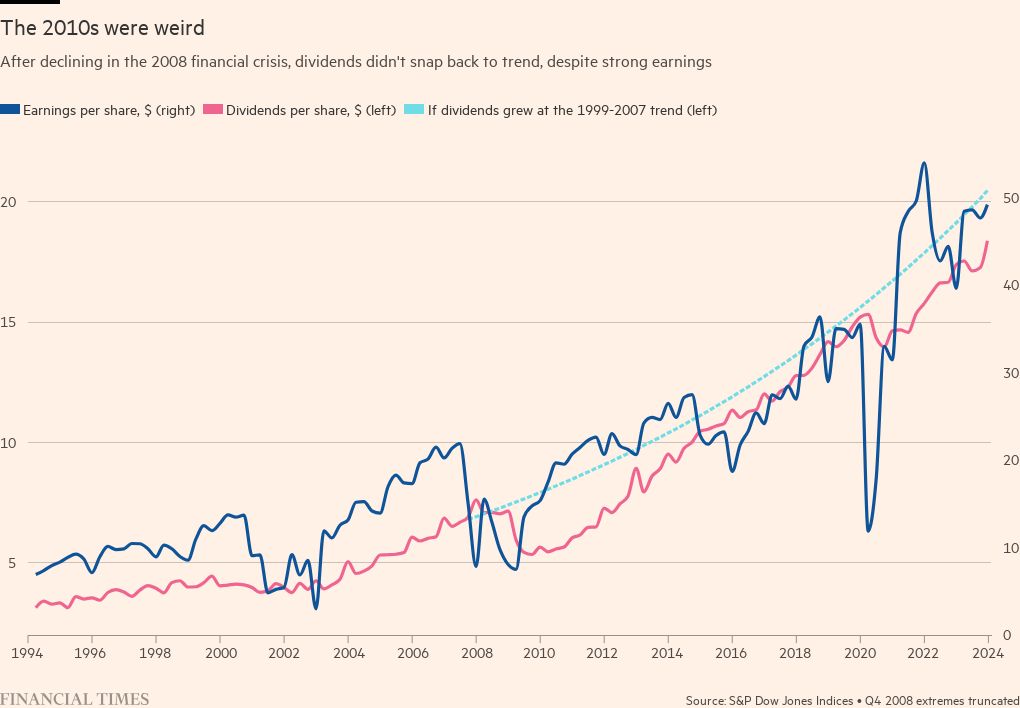

This is all well and good, but the data tell a subtler story. The dividend may be set for a comeback, but it certainly isn’t back yet. Start with some high level numbers, courtesy of S&P’s excellent Howard Silverblatt. Dividends took a notable step down after the great financial crisis, relative to earnings per share, and have never fully rebounded:

Silverblatt also notes that dividend growth slowed to 6 per cent in 2023, down from a roaring 10 per cent in 2022. This reflects general corporate caution, he says. Although huge earnings growth in 2021 underpinned new dividend announcements in 2022, since then the economy has been remarkably hard to read. Unlike buybacks, which can be stopped on command, “dividends are a pure cash flow item”, says Silverblatt. “You need to keep it up for two, three, four quarters, or longer. And it wasn’t so long ago that you had strong odds of recession and a ‘soft landing’ meant anything that wasn’t a nosedive.”

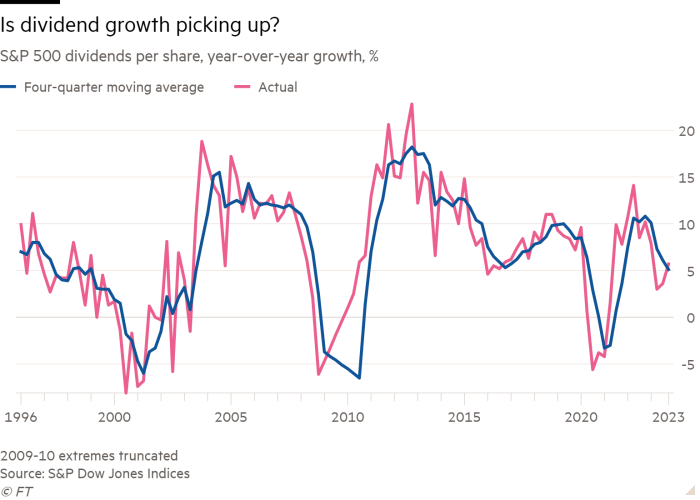

A slight pick-up in the back half of 2023 gives grounds for hope. The chart below shows year-over-year change in S&P 500 dividends. The pink line is quarterly variation, while the blue line is a slower-moving average. The quarterly data is noisy, but you can see a little tick up in the pink line:

Wall Street Horizon, a data firm, notes a sharp pick-up in the number of companies announcing dividends in January (though their sample is global). That includes 56 S&P 500 companies, which announced dividend increases averaging 6 per cent, according to Goldman. Moreover, February is generally considered the busiest month for dividend increases, coming after year-end balance sheet clean-up but before big investor events. The good news could keep coming.

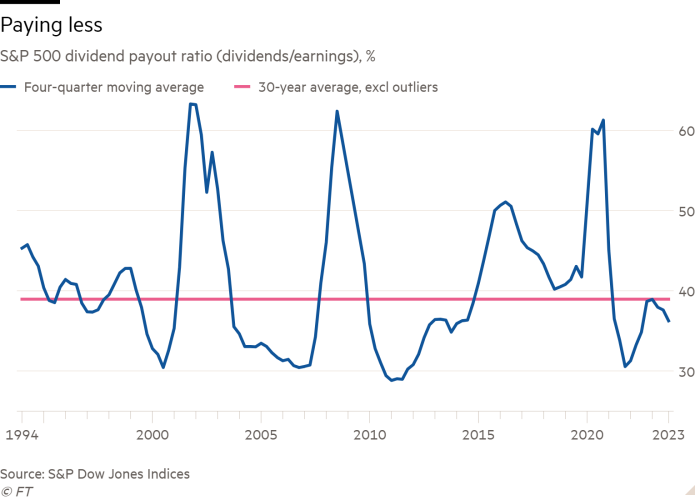

Another place to look is the share of earnings that companies distribute in dividends — the payout ratio. It plummeted after the pandemic, but has since staged a recovery to just a bit below the 30-year average:

The point here is companies’ dividend payments are not particularly high relative to earnings, suggesting scope for further increases.

In sum, this looks less like a dividend renaissance than a few encouraging trends that could be easily reversed in an economic soft patch. (Ethan Wu)

One good read

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, hosted by Ethan Wu and Katie Martin, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.