Three years ago, British private equity firm Cinven was forging ahead in its quest to buy up chunks of Europe’s sleepy life insurance sector.

The buyout group owned mid-sized life insurers in Italy and Germany that it had expanded aggressively in an era of low interest rates, buying up books of annuities offloaded by other insurers.

A new €1.5bn fund, its first targeted specifically at financial services companies, would capitalise on Cinven’s “proven track record” investing in the sector, said Caspar Berendsen, a senior dealmaker at the private equity house, who co-led the strategy.

Its investment in Eurovita in Italy was on track to be moneymaking, Cinven told investors. The firm was so bullish on its German life insurer, Viridium, that it shuffled the asset between funds, a move that allowed it to extend its ownership and continue to pursue the group’s consolidation strategy.

The plan has since fractured. Eurovita fell into administration last year, as rising interest rates exposed balance sheet weaknesses. Cinven did not put in all the extra capital the regulator wanted, and the insurer’s policyholders rushed for the exit.

Berendsen left the firm later in the year. He declined a request for comment.

Then a banner deal from Viridium to acquire a $20bn back-book from Zurich collapsed in January. Germany’s financial regulator had been poised to block the deal on concerns over events at Eurovita and the private equity-fund ownership structure, according to people familiar with the matter.

That has thrown the private equity-backed insurance roll-up strategy into doubt, according to a person familiar with Viridium’s view: “It is clear that we can only keep growing if there is an ownership structure that BaFin will allow.”

Cinven declined to comment. A person familiar with Cinven’s position said it contributed significant capital to Eurovita, including buying back bonds as part of the liquidation, and that Viridium had a strong financial position.

The events, executives say, amount to the biggest challenge yet to private capital groups’ foray into the life insurance sector.

One adviser to private capital groups said the Eurovita episode meant it was “one step forward, three steps back” for private equity’s standing with regulators after years of trust-building.

“The big question is, can the PE firms be a trusted owner of a life insurance company?” said Isabelle Santenac, global insurance leader at consultancy EY. That comes with taking “responsibility when there is a problem and [continuing] to inject capital and to sustain your subsidiaries”, she added.

Private capital groups have swept into life insurance since the financial crisis, with firms as big as Apollo, Blackstone and KKR either acquiring life insurers — providers of annuities and other products — and reinsurers, or striking strategic partnerships.

They found willing sellers in traditional insurers looking to dispense with capital-intensive business. Private capital investors have acquired more than $900bn in life and annuity assets in western Europe and North America, according to McKinsey & Company. This gave them access to a vast amount of assets that could be steered into private credit and other higher-yield assets to match insurers’ long-term liabilities.

Encouraged by the Eurovita collapse, policymakers, regulators and some investors are now urging greater scrutiny of the special risks to insurers and their millions of policyholders created by this shift.

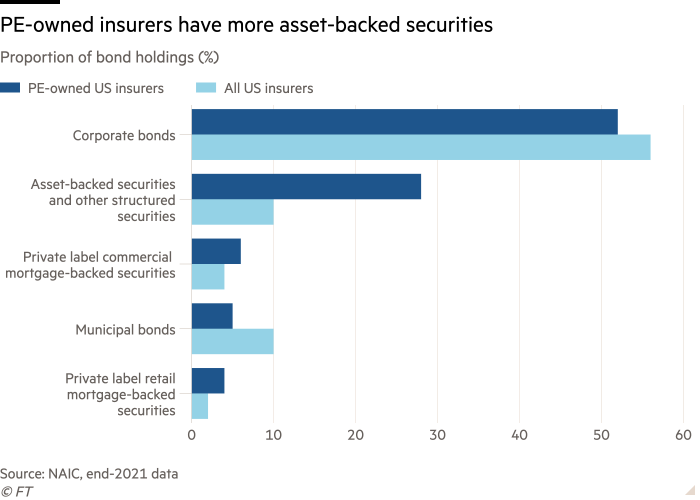

The IMF is urging regulators to consider the risks to the financial system posed by insurers either owned by — or whose assets are managed by — private equity groups. It calls them “PE-influenced” insurers. Such firms, it said, were “more vulnerable” to a credit downturn, due to their higher proportion of illiquid assets, a situation that could be “aggravated” by the embedded leverage in structured credit.

Jonathan Dixon, secretary-general at the International Association of Insurance Supervisors, told the Financial Times that while the sweep of private capital groups into the life insurance sector helped “fill a gap” left by traditional investors, it had “raised concerns about conflicts of interest, increased risk-taking, and internal governance that require enhanced supervision”.

The shift in ownership, he said, had brought with it greater allocations to illiquid assets and increased use of reinsurance deals that see assets moved offshore.

“These structural shifts have the potential to contribute to increased liquidity, credit, recapture and concentration risks in the sector,” he added. The IAIS has warned that the “structure by which PE-involved firms own and influence insurers tends to exhibit complexity and opacity, which makes both the identification and monitoring of key risks more difficult”.

Ownership structures have crucial differences, stress executives at private capital groups. They contrast a PE fund owner such as in the Eurovita example — where a short-term investment horizon and structure might clash with a life insurer’s needs — with an insurer that sits on the balance sheet of a big finance group, such as Apollo’s Athene or KKR’s Global Atlantic.

Blackstone, meanwhile, has opted against owning insurers outright, instead taking minority stakes alongside deals to manage their assets.

In Europe, Cinven’s problems have underscored the risks of the first model, they say. “All EU regulators are really down on PE fund owners right now,” said one insurance executive.

Private capital groups argue their ownership has made life insurers stronger, providing vital capital to the sector. When it bought the remainder of insurer Global Atlantic in November, KKR said the unit’s assets under management had risen in the time it has served as asset manager from $72bn in 2020 to $158bn in 2023.

Private capital executives argue that taking some liquidity risk, with strict asset-liability management, is a safe option. Athene’s fixed-income portfolio is 97 per cent investment-grade rated.

Still, others worry about where the sector’s changing investment strategies could lead. “I am concerned that this trend in insurance investment may mirror the risk-taking behaviour financial institutions undertook that led to the financial crisis and had spillover effects across the economy,” US senator Sherrod Brown warned government officials in 2022.

One area of focus has been a reliance on securities such as collateralised loan obligations — packaged-up corporate debt — to back insurance liabilities. US regulators are considering tighter capital requirements on such assets, supported by traditional insurers such as Equitable.

The spotlight has also fallen on Bermuda, where private equity-linked reinsurers have entered into transactions with primary insurers in other territories.

Regulators are scouring reinsurance deals that move some of the assets backing promises to policyholders offshore to a regime that, though deemed equivalent with European solvency rules, is viewed as more flexible on investments. In the UK, the Bank of England has proposed limits for so-called funded reinsurance deals.

Some Bermuda-based carriers have drawn particular attention, including a reinsurer linked to Everton FC bidder 777 Partners. The reinsurer served as the “primary balance sheet” for 777’s asset management strategy, according to a 2021 investor document seen by the FT.

US insurance group A-Cap said last month it would attempt to raise capital and take back control of assets that it had ceded to 777 Re after downgrades of the reinsurer, putting pressure on the funding structure behind 777’s series of high-profile sporting acquisitions. The downgrade came from AM Best, the specialist rating agency, citing a significant rise in exposure to “less liquid affiliated investments”.

A list of related-party investments, for example one related to Canadian low-cost carrier Flair Airlines in which 777 invested in 2018, is included in 777 Re’s annual accounts.

The Bermuda regulator declined to comment. 777’s founder previously told the FT that 777 Re was working to reduce its holdings of illiquid assets but did not need more capital and had “done absolutely nothing wrong”.

Others push back against this being a Bermuda problem.

It is “agnostic of location”, one senior insurance figure in the UK said. “[Private equity owners] will pop up in any jurisdiction, they will chance their arm.”

How Cinven’s life insurance strategy ran into problems

In the wake of the financial crisis, Cinven spotted an opportunity to consolidate closed books of life insurance. In 2011, the firm bought Guardian Financial Services from insurer Aegon for £275mn, intending to consolidate the UK industry. The bet paid off and Cinven sold the company about five years later for £1.6bn.

In 2014, Cinven acquired Viridium, formerly Heidelberger Leben Group, in Germany. A few years later, they acquired Eurovita from investment firm JC Flowers in a €300mn deal. Cinven now had hundreds of millions of euros staked on the sector.

Eurovita and Viridium launched aggressive acquisition strategies, boosting assets and policy numbers. But Eurovita foundered when interest rates jumped in 2022. Customers rushed to cash in their policies, causing a liquidity crisis. Afterwards, Italy’s central bank said Eurovita had suffered from “inadequate risk management, limited capital and shareholder disengagement”.