In Cambridgeshire’s fertile Fenlands, Luke Abblitt was unable to get all of his potatoes out of the ground this winter because of the record rainfall that has lashed the UK over the past year.

“The knock-on effect financially is harrowing,” said the tenant farmer, who sells about 13.5 tonnes of the staple to fish and chip shops every week alongside other crops.

Abblitt has also struggled to plant all his spring crops. “We either can’t combine because it’s too hot . . . or it’s too wet and you can’t do anything,” he said.

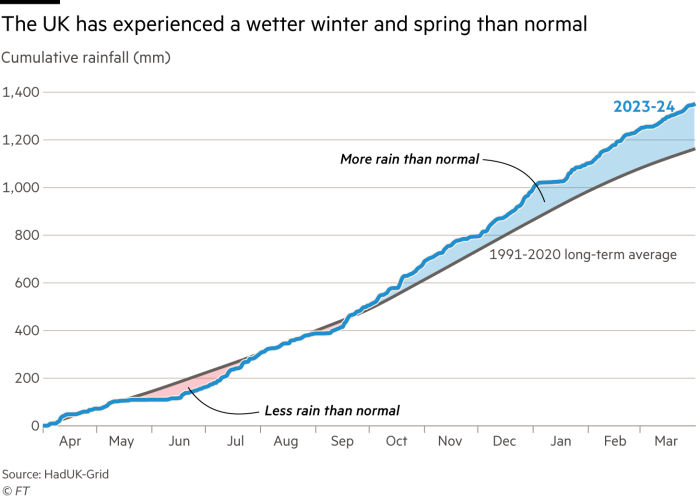

According to the Met Office, England has just experienced its wettest 18 months since 1836. This week the National Farmers’ Union called on the government to boost support for growers affected by heavy rain earlier this year, which has left swaths of agricultural land flooded.

As the national weather service predicts warmer and wetter winters, farmers have warned that the UK’s food security — and their own profitability — is under threat.

“It’s not about empty shelves, it’s about long-term security of supply and investment,” said Jack Ward, chief executive of the British Growers Association.

Supermarkets keen to keep prices low for squeezed consumers could look elsewhere to ensure a steady supply of fruit and vegetables, said Ward. But the UK needed to ensure its own supply in case of shortages on the continent, which are increasingly common, he added.

Ministers have pledged to maintain the proportion of homegrown food consumed in the UK at its current level of 60 per cent. In February, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak vowed to publish an annual “food security index”, as part of a push to win over rural communities ahead of the election.

European farmers have been hit equally hard by more extreme weather, while the implementation of the post-Brexit border with the EU has made trading with the UK more costly and complex.

“Margins on the continent tend to be better than with UK retailers because people pay more for their food. So if you’re a Spanish or Italian supplier then there is less incentive to send [your produce] to the UK,” Ward said.

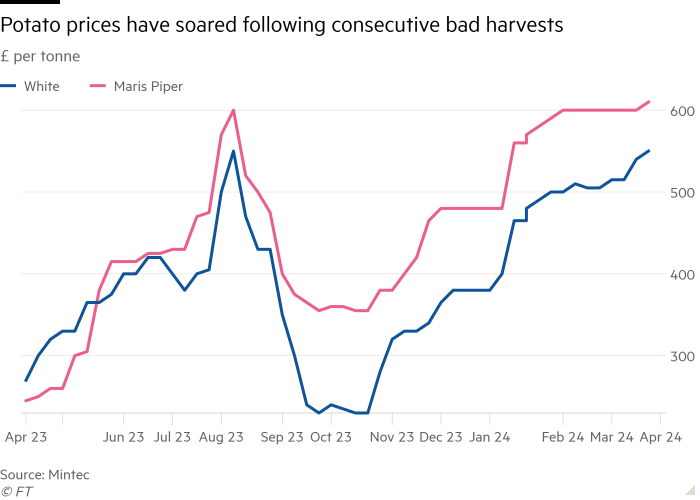

Last year’s wet harvest forced some potato growers to leave crops in the ground, and much of the produce brought up from the soaked soil was not of sufficient quality, resulting in short supply and high prices.

Abblitt said he and his colleagues at Daintree farm typically finished harvesting potatoes before Bonfire Night on November 5. Last year they were still harvesting well into December.

“If they go in bad condition, with a lot of muck in the boxes . . . they start breaking down,” he said. “All you can do is try and get rid of them earlier, but there was a glut because everyone was doing the same thing, so we couldn’t get a good price for them.” The same could happen this year.

“A delayed 2024 harvest would mean the limited supply would need to be stretched out further, driving prices higher as the market year progresses,” said Harry Campbell, fruit and vegetable analyst at data provider Mintec.

The tight supply has led some supermarkets to make up the shortfall with potatoes from the EU, Egypt and Israel. Others were not willing to shoulder the costs of importing produce, Campbell said, but were instead using up the domestic supply until a new crop was available. This has pushed the farm price to highs of £600 a tonne for Maris Pipers.

In its early survey of this year’s harvest, the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board, an advisory body to farmers, found excessive rain had caused big declines in planting of crops such as winter wheat, winter barley and oilseed rape.

The amount of arable land left unsewn so far in the 2024 harvest had rocketed by almost 80 per cent compared with the 2023 harvest, according to AHDB.

Scott Walker, chief executive of trade group GB Potatoes, said six years ago potato farmers produced 6mn tonnes of the vegetable each year but “now we’re looking at 4mn tonnes”.

“If you’re not guaranteed a consistently good return, farmers will look at using the land in a different way,” he said, adding that farmers needed more support from the government to build resilience against droughts and flooding.

Ministers this week announced they had made available grants of between £500 and £25,000 for farmers affected by storm Henk in January. But the NFU, which has 46,000 members, said the fund had “major issues” and that many affected by the flooding were not eligible for support.

In the meantime farmers’ incentive to plant spring crops is fast diminishing, increasing the risk of shortages later this year.

The prices farmers can command for crops including grain and oilseed have fallen more than their input costs, such as fertiliser and fuel, according to AHDB. In addition, wet weather means fields are not drying out in time for farmers to sow seeds.

“It’s unclear if all the intended spring crops can be planted,” wrote the advisory body in its early harvest report, adding that farmers concerned about profitability were turning to environmental schemes that would win state subsidies, such as tree planting and rewilding.

Abblitt said he would like to be able to adopt more environmental farming practices such as cover cropping, where non-cash crops are planted to help regenerate the soil, but said there was no guarantee he would be able to maintain his current yields.

“Who is going to bridge the gap?” The single farm payment . . . always came through and that saved us in some years,” he said, referring to the EU subsidy scheme that applied before Brexit. The UK’s new scheme rewards restoration of the natural environment and adoption of sustainable farming practices.

“Now you’re on your own. You want me to farm efficiently, greener and for less money? If you’re going to treat me as a business, I will farm like a business.”

Ward of the BGA said the squeeze on farmers was leading to rapid consolidation of farms into just a handful of producers, and that every part of the supply chain needed to take sustainable production seriously.

“If you look at retailers, its all about price cuts,” he said. “But in reality the cost of growing food is going up not down. You can’t turn your back on increased production costs.”