Strange “hairy” covers of books in medieval Europe were made from seal skin obtained from Viking descendants, a new study has found.

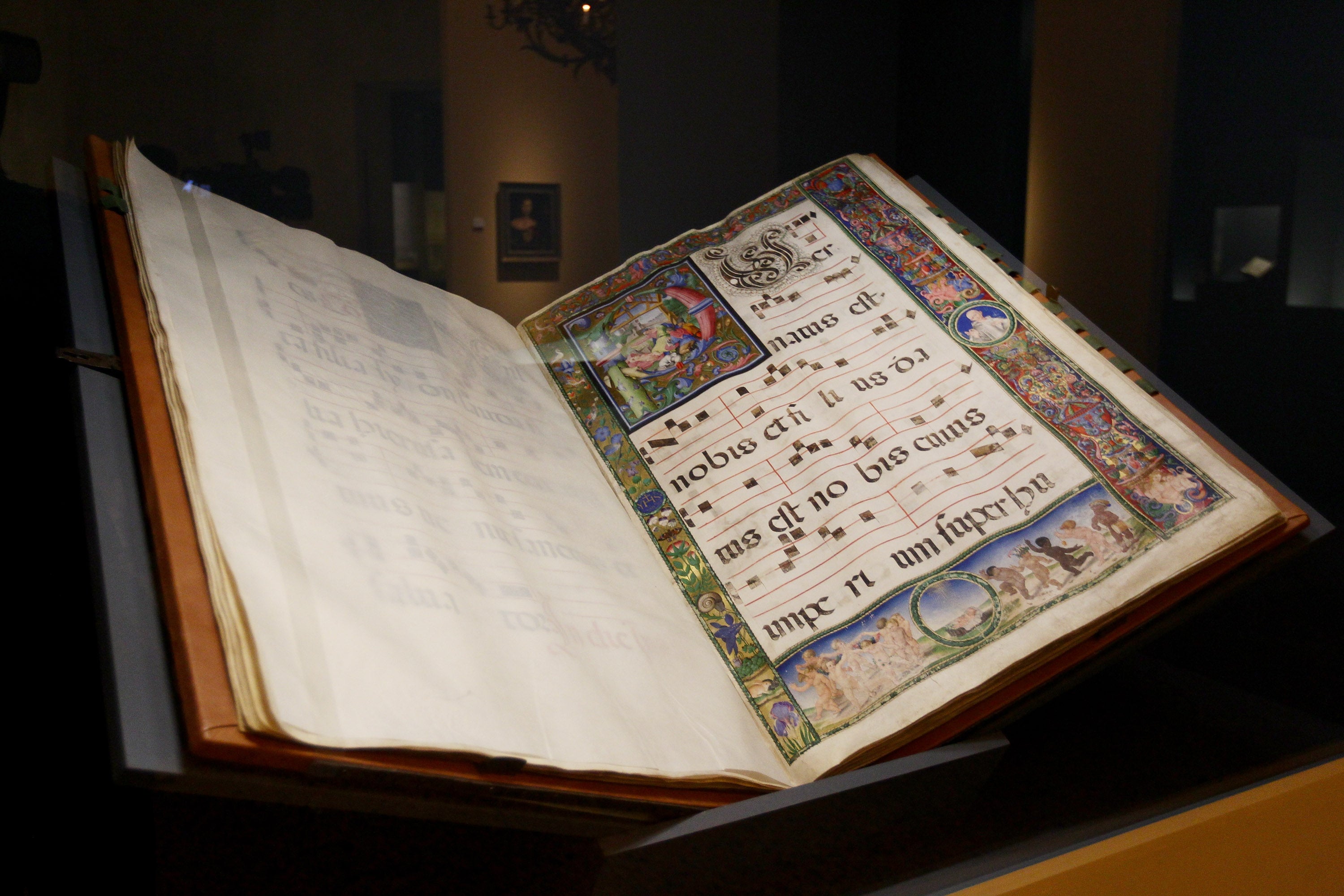

It is rare to find medieval manuscripts in their original bindings, but some from the 12th and 13th centuries have been preserved in Cistercian libraries such as Clairvaux and its daughter abbeys.

The Clairvaux Abbey in Champagne, France, holds nearly 1,500 medieval books written by scribes of the Cistercian Catholic religious order.

For a long time, the exact material that was used to make these manuscript covers, called chemises, has remained unclear.

Now, scientists subjected over a dozen of these book covers to diverse analysis techniques like mass spectrometry and ancient DNA analysis to find that seals were the source of these bindings.

Researchers also analysed another 13 “hairy books” from Cistercian “daughter abbeys” in France, England and Belgium and found that these were also bound by seal skin material.

DNA analysis revealed that eight of the skins were from harbor, harp, and bearded seal species likely sourced from their populations in Scandinavia, Scotland, Iceland, Greenland, and “perhaps Barents-White Sea region”.

The findings suggest the Cistercians were linked to wider economic circuits, including fur trade with the Norse descendants of Vikings. However, there is no existing written record of the purchase or any use of sealskin at Clairvaux Abbey.

“We have no written records to explain why monks chose to cover these manuscripts in sealskin, nor can we determine if these covers were a sign of particular value or symbolism,” scientists wrote.

The Norse trade network may have also been involved in transporting walrus ivory from the far north into continental Europe, scientists say.

“The widespread use of sealskins in Cistercian libraries such as Clairvaux and its daughter abbeys during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries hints at broader trade networks,” scientists wrote.

“This geographical inference supports the notion of a robust medieval trade network that went well beyond local sourcing,” researchers write.

However, seal skin use in bindings appears to have ended just before 1300.

Researchers suspect this could be due to the Little Ice Age, which caused Norse settlements to disappear from Greenland.

“Norse hunting methods in the Arctic were not well suited to the increased sea ice resulting from climate change,” scientists wrote. It also remains unclear if the Cistercian monks knew that the fur they obtained on the market was from seals, which they described as the “sea calf”.

The mammal was rarely depicted in medieval art, and neither did it hold a place in heraldry.

“This lack of representation might have contributed to a detachment from the animal’s true identity, making it difficult for contemporaries to recognise sealskin as a specific material,” researchers say.