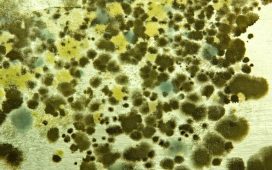

Issues such as population decline, environmental concerns, resource extraction, economic uncertainty, and declining public services are common in the Arctic. Photo: Tetiana Shyshkina

Arctic communities and organizations have successfully drawn the attention of international communities, as well as fostered collaborative efforts among each other to address issues that affect the region collectively and create a space to share knowledge and information on research and policies to enable further growth of the region. The discussions between Arctic organizations and institutions usually involve discussion of challenges such as declining population, the positionality of Indigenous knowledge, expediting global socio-economic and environmental changes, resource extraction, ecosystem degradation, climate change vulnerability, and Arctic community resilience.

The focus of this article is on the climate policy implication and internalization of policy implementation across generations. Some scholars argue that Arctic communities and Indigenous peoples have been designated as the representatives and representations of accelerating climate changes in the world. This representation as climate change representatives exists beyond the collaborative and joint efforts of Arctic organizations and institutions to create awareness of these rapid changes, it goes further into the discussion on the adaptation and resilience of the Indigenous peoples and the Arctic population towards the policy implementation, their perception about climate change and the consequences of policies on the Arctic populations. This designated attribute, therefore, represents the Arctic population as a key unit of analysis to properly understand the perception of climate change and climate policies among its population and along generational lines.

The Arctic and Indigenous organizations and institutions have also succeeded in creating a dominant media and socio-political presence, a key feature that has enabled the region and various stakeholders to communicate with the global community a message about the effect of climate change on itself and its people. As we discuss the properties of this media representation and activism about the effect of climate change in subsequent sections, it is worthy to note that media representation and activism are a visible product of both awareness creation and media activism towards the socio-political dimensions of this effect of climate and environmental changes in the Arctic.

This article will provide an exploration of behavior and perception among the Arctic population and Indigenous peoples across generational lines towards climate change, then expose the reader to the presence and trends of media representation and activism concerning adaptative and resilient behavior towards the effect of climate change and policy implications. A discussion on the merits of the use of generational theory to understand this behavior would follow and then finally discuss and explore the practical solutions that would prove useful to policymakers.

As this paper proceeds to explore generational differences in the perception of changes, it must provide certain operational definitions of certain keywords. First is the concept of climate change, this article defines climate change as long standing shifts in weather and temperatures that produce manifest and salient changes observable to people. These changes usually generate perceptions and actions towards resilience and adaptability.

Generations refer to a collective of people born around a certain time. The term generation in popular culture is grouped into Baby Boomers, Generation X, Generation Y, Generation Z, and Generation Alpha. It is also a widely used grand theory referred to as the generational theory. An example is the Strauss-Howe variation of generational theory, and others. In this paper, we use the term cohorts to group people who share a similar experience of climate change. Using cohorts enables a classification across age groups rather than using generational groupings. Cohorts were used in the work of Herman-Mercer et al with grouping classified as Cohort 1 (18-29), Cohort 2 (30-49), Cohort 3 (50-64), and Cohort 4 (65 and older) to aid the analysis of data collected.

Adaptative and resilient behavior research across generational lines in the Arctic

Climate change is rapidly affecting policy-making and policy implementation in Arctic communities. With diminutive time to create adaptative structures, characterized by different systems, different Arctic communities have structures and perceptions on how to adapt to the changing environment and their future in the Arctic region. Adaptation and resilience to climate change are therefore unique to each Arctic region, and its population.

Adaptative research over the years has used different perspectives. In the adaptative research of Herman-Mercer et al in sub-Arctic Alaska, adaptation was analyzed from a cultural perspective, a choice defended by Herman-Mercer et al as a perspective that produces actual results that best qualify the perception of the Arctic Alaska population. Another study by Dankel et al in Longyearbyen, conducted adaptative research using an approach that generates plausible scenarios and engages in a reflective discussion with stakeholders, and policymakers to design a framework that would bridge the science-policy gap in the Arctic policy implementation. In Ford et al on the Canadian Arctic, adaptative features are rapidly changing in the community as a whole and along different generational lines. This research is similar to other research including Stepien et al and Rybråten et al all performed examinations of the perception of adaptation to climate change with different perspectives of analysis.

Generational differences are bound to exist within any spectrum including climate change and its adaptative behavior. These differences are of key importance in analytical procedures and giving recommendations. Drawing influence from these empirical studies on adaptation and resilient behavior particularly in the Arctic and subarctic regions, it is important to categorize the common elements of this behavior across the generational line. To provide a comprehensive understanding of the reasons for such generational differences and the effect of the changing perception and adaption across generations, we would discuss the generational theory as a tool that can aid in the explanation of these changes in adaptative and resilient research across generational lines.

Method

A systematic review of existing literature would provide explanations of the focus of the article, thus the choice of this method. The core focus of this article is to supply an inclusive analysis of the use of generational theory using cohorts on the presence of generational differences in the perception of policy implementation and environmental changes because of climate change. The question therefore is: In what way can generational analysis analyze the perceptions of changes in Arctic communities as shown in the selected studies?

We have chosen to systematically analyze the studies shown in the table below to provide answers. This article chose these listed pieces of literature over others for two basic reasons. First is their study reporting the presence of generational differences in climate change perception. The other reason is the location of these empirical studies in the Arctic and subarctic regions. Other pieces of literature and analysis will also be used during this systematic analysis, with three out of these listed four empirical studies reporting generational differences in the perception of climate change, making this choice efficient for the analysis of this article.

| Authors | Title | Study Population |

|---|---|---|

| Nicole M. Herman-Mercer, Elli Matkin, Melinda J. Laituri, Ryan C. Toohey, Maggie Massey, Kelly Elder, Paul F. Schuster, and Edda A. Mutter | Changing times, changing stories: generational differences in climate change perspectives from four remote Indigenous communities in Subarctic Alaska | St. Mary’s, Pilot Station, Kotlik, and Chevak, Alaska |

| Dorothy J. Dankel, Rachel G. Tiller, Elske Koelma, Vicky W. Y. Lam and Yajie Liu | The Melting Snowball Effect: A Heuristic for Sustainable Arctic Governance Under Climate Change | Longyearbyen, Svalbard, and Bergen, Norway |

| James D Ford, Barry Smit†, Johanna Wandel, Mishak Allurut, Kik Shappa, Harry Ittusarjuat and Kevin Qrunnut | Climate change in the Arctic: current and future vulnerability in two Inuit communities in Canada | Arctic Bay and Igloolik, Nunavut, Canada |

| Stine Rybråten, Maiken Bjørkan, Grete K. Hovelsrud & Bjørn P. Kaltenborn | Sustainable coasts? Perceptions of change and livelihood vulnerability in Nordland, Norway | Lurøy, Rødøy, Vefsn, Alstahaug, Brønnøy, Nordland, Norway |

Findings and discussions

The studies selected (see Table above) present a crucial view of current empirical analysis on the generational perspectives on the existing perception of climate change. Herman-Mercer et al conducted an intensive exploration into these generational differences by dividing the study population into cohorts to properly distinguish and identify these changes. Using cohort as a basis of separation reveals the cohort and time interval effect play in climate change perception. Their analysis reported this through its observation of participants’ expressions of manifest climate changes in their environment during various seasons.

The time interval effect is manifested in summer and winter as changes during seasons are highly noticeable. The common cohort effect in this analysis is the means of economic subsistence (hunting, fishing) and weather conditions (snow, rain, wind, and sun). This cohort effect in this research although conducted in Alaska shares common features with Svalbard as enumerated by Dankel et al in their advocating for a framework that would aid policymakers to address climate change complexities.

Dankel et al conducted a less intensive generational analysis and more intensive stakeholder participation. This research included various stakeholders across generations which he divided into the older and younger generation. The cohort effect in this research as expressed in the scenario used to interview participants thoroughly examined the social, economic, political, ecological, and governance aspects of climate change. The important cohort effects among generations here as well were economic and future concerns.

Herman-Mercer et al conducted a generational analysis that provides this research with actual reports on these perceptions while Dankel et al, and Rybråten et al conducted a stakeholder analysis on the environmental, socioeconomic, and socio-political changes that occur because of climate change. Therefore, providing this analysis with a distinct perspective on the generational views or explanations of the changes from stakeholders. Although Ford et al analyzed vulnerability and adaptation, a clear-cut distinguishing generational analysis was not visible even with its expression of a certain generational undertone.

Policy implementation in the chosen study area

The common policy implementation and its perception implication in the chosen area of study across selected research (see Table above) are displayed below:

- The available adaptative technology supplied to mitigate changing environmental conditions is perceived by some cohorts as something which erodes Indigenous culture and deprives the younger cohort of developing adaptative capabilities.

- The inability of proper protection provided for local primary industries to support Indigenous businesses enables larger companies to infiltrate Indigenous markets. This infiltration costs local businesses economic capacity to recruit younger cohorts into the profession, and to strengthen Indigenous knowledge and expertise.

- The resource development in Arctic communities in Canada (Arctic Bay and Igloolik), in Svalbard, as well as the development of tourism in Arctic communities, and other forms of commercialization of particularly remote Arctic communities are seen by some as policies that may impede the adaptative capability of the Arctic population and present further future vulnerabilities, and to others as policies that may improve economic standings of the region.

- Expression of future vulnerabilities particularly towards Indigenous produce such as fishing and animal rearing, and the effects it may have on the Arctic population.

The articulation of this policy implication on the Indigenous population is an expression of changes in the environment to which the Indigenous population is developing adaptative capability and resilience. The perception of these changes and policies differs within cohorts, many of them develop a further interpretation of policies because of the changes policies have on their environment and the perceived future vulnerabilities that they could be exposed to. Their assessment of vulnerabilities to changes and policies is discussed in later sections in a division between older and younger cohorts.

Assessment of vulnerability and resilience to climate changes in the older cohort

The older participants (locals and stakeholders) presented a persistent high observation of changes. Herman-Mercer et al reported drastic observations of change in the environment by the older cohort (Cohorts 2, 3, & 4). This was attributed to their ability to notice the physical changes, while the younger cohort’s understanding of changes was based on historical materials, such as stories, pictures, and many more. Another common discussion within the older cohort reported by Rybråten et al among stakeholders was the growing concern for preserving the environment and lifestyle with a hint of fear for the future with a not so bothered younger generation.

Another assessment shared by Herman-Mercer et al, Ford et al, and Rybråten et al was the expression of dilution of social and economic lifestyle due to the development of technology that usually encourages risky behavior, their inability to recruit younger cohorts into the community primary industries, as well as lack of governmental support on recruiting and retaining younger cohort.

The older cohort in Dankel et al expressed the need for policies to regulate Indigenous produce, especially fishing in the region of northern Norway. However, in line with Coates & Holroyd’s discussion on Arctic policies, Rybråten et al explained that subjects reported that policies that push local businesses to increase productivity are usually more favorable for larger companies to comply. This, therefore, deepens the inequality that policies level on local businesses, which in turn makes many local businesses short-lived and deprives the younger cohort of gaining Indigenous knowledge and expertise.

Policies in this manner have been perceived by Indigenous producers as a tool for inequality between local businesses and large corporations. Another example of policies being perceived as a risk toward adaptative capacities is in the Indigenous Igloolik and Arctic Bay communities, where they perceive education strategy/policy as a tool that erodes the younger cohort of Indigenous practices (both cultural and economic practices) and therefore diminishes their future adaptative capability.

Assessment of vulnerability and resilience to climate changes in the younger cohort

The most common feature associated with the younger cohort was the recognition of change as a constant factor. Dankel et al reported staunch support for compromise and resilience within the younger cohort subjects. One could attribute this feature as an indicator of evolution within the younger cohort as an effect of constant changes in the environment (Arctic environment particularly).

The concerns about the changes in socioeconomic lifestyle were also conveyed by Rybråten et al, who stated that the changes due to climate and governance strategies were a threat to the livelihood of local businesses in the Arctic region. They believed that if strategies facilitate development from within, where there is a deep sense of community connection, to improve knowledge sharing, trust-building, and stronger development of Indigenous expertise and knowledge that would aid adaptation to their environment. A sentiment deeply shared with the participants in the research by Ford et al. This expression from this research shows the deep level of responsibility expected from the younger cohort to maintain standards despite these constant changes.

Adaptative strategies as identified by Ford et al usually bear anti-social costs which are detrimental to the development of resilience within the younger cohort. Also, huge financial costs to procure certain adaptative technologies deter the participation of younger cohorts, thereby developing inequality of adaptative capacity, especially in the younger cohort.

Media activism

Media is a forum used to debate climate change as well as provide information on climate changes around the world. Since this paper focuses on the generational activism of media on climate change, we would begin by describing the concept of media activism. Media activism in this paper refers to social action and advocacy measures towards certain challenges prevalent in media spaces across the globe. Advocacy and social action measures in media spaces on climate change are examples of media activism on climate change.

Climate change media reporting hitherto has been categorized into four major frames. These frames are prevalent in all media spaces, both broadcast, and digital media spaces. The observed frames are summarized as:

- Climate change as a global crisis

- The ambiguity of science regarding climate change

- Climate change as a deterrence to economic advancement

- Ecological transformation

The common feature of research on climate change is the presence of political influence and policy implication in both the representation of climate change in media spaces and the perception of these changes. Political and state actors are often involved in discussions within these listed frames, making media spaces a useful tool for perception communication and discussions of frames. Since there are not many intensive studies on the generational representation of climate frames in media spaces, we cannot provide a direct link between generational perceptions and media activism. However, this paper will explore the link between stakeholder perceptions and climate representation in media spaces.

Drawing influences from the stakeholder’s positions in Rybråten et al and Dankel et al the frames that suit their perspective on climate change range from climate change being a global and regional crisis to scientific uncertainties. As Ryghaug and Skjølsvold put it, the acceptance of climate change as a crisis but with doubts on how to progress on addressing the issue.

The point made by Ryghaug and Skjølsvold is very intriguing to examine in a social context. In the research conducted by Kaltenborn et al to uncover the themes of news coverage in the chosen area of study in northern Norway, the themes of news coverage analyzed in northern Norway differs from themes of the circumpolar High North news, with climate and environmental changes ranking the top three of prevalent themes from news reporting while the latter ranking climate and environmental changes the bottom four. This goes to show that the Arctic population recognizes climate change but with scientific ambiguity, economic growth concerns, and doubts about measures to take to address the crisis.

This ambiguity of the overall approach toward climate change is observable in the perception of the younger cohort. As Herman-Mercer et al explained, it is expected that the younger cohort whose entire lifespan is characterized by the Arctic warming trend and a lack of a consistent plan to address this crisis facing the Arctic population. Although research has not linked this as the reason for a low percentage of change in observation, ambiguity does have an influence. Another influence on the younger cohort may come from media representation and frames, the presence of this ambiguity may be a leading cause of their lack of observation.

Concluding discussion and recommendations

This paper has reviewed the results from the already existing empirical analysis of these perceptions and made obvious the generational undertone of various research using cohort analysis. From our analysis, certain problems are clear within the expressed perceptions, therefore providing this research the ability to recommend to policymakers and researchers. It is indeed obvious from our findings and discussions that generational perceptions are understudied, therefore imploring more researchers to include this variable where applicable in later research.

This paper also wants to bring the attention of policymakers to the importance of trust-building between all stakeholders. In Hamel et al the importance of engaging stakeholders was clear. This paper describes the strategic process of involving stakeholders, a similar strategy employed by Dankel et al for developing a framework for anticipation, engagement, and reflection. This paper fully understands the need for strategic trust-building between stakeholders.

Rybråten et al expressed the importance of understanding existing values within existing stakeholders of climate and environment changes and just as the work of Dankel et al and Hamel et al show the importance of communication, networking of stakeholders, and provision of institutional support and arrangements to these groups.

This paper encourages the creation of a structure within these stakeholders’ groups and projects that observes varying interests from various stakeholder groups or even varying generations. If this structure exists within groups and projects, the resolution of these variations and perceptions can be managed by both researchers and policymakers as they now have the materials to which they can approach existing variations of problems, a method that would provide researchers with the knowledge of existing variation that they can research about, and also bring to the attention of policymakers that the common interests and goals in these projects are not the only existing opinions. This idea would further strengthen Indigenous interest, and could further aid the avoidance of conflict in the High North as implied by Østhagen.

Amundsen and Hu and Chen with their study on place-based communication and experiences that contribute to place attachment, particularly within the age ranges of the younger cohorts are another influence on our recommendation. This may enable them to be more interested in climate discussions, deter outmigration, and express their perception of environmental changes and policy implementation on climate change. Place attachment can be a prerequisite for forming perceptions and expression of opinions that may be a tool of use to policymakers in addressing the limited expression of perceptions and opinions from the younger cohorts. The use of place-based experience and narrative to express opinions can be reanimated to supply climate change education across generational lines. If people have a certain attachment to their place of living, climate change education and climate policies can be more tailored toward their attachment narrative and experience.

We have emphasized the importance of communication during stakeholders’ networking, and trust-building, and during our discussions on media activism and coverage of climate change. Policy and climate change communication are intertwined. Ryghaug and Skjølsvold and Pinto et al have shown this extensively in their work on climate change communication in Norway and across the globe. It is indeed an understood subject that there are very polarized varying views on climate change, policy implementation on climate change, and climate change reporting in the media. One way to address these problems could be through efficient policy communication.

Policy communication is important as it informs the opinion of several stakeholders on climate change. As this author emphasizes, there is a need to depolarize information within media spaces. Context and complexities are crucial factors within communications. Objects and subjects of reporting have specific contexts and exist within specific complexities, these contexts are important to understanding the information reported. Communication models on climate change reporting should be redesigned to communicate the context and complexities to readers.

Media spaces are an important source of information for stakeholders, therefore information excluding contexts and complexities could erode ethical media reporting and further widen the space between science, policy, and people. A communication model that could integrate science, policy, and people and communicate context and complexities could be a way to improve climate change reporting.

Shukurah Oluwatobi Lawal is an Early Career Researcher at the Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø (UiT).