Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The UK should consider a range of technologies for future large-scale nuclear power plants as it seeks to revive the sector, according to the top official overseeing those efforts, casting doubt over the country’s long-standing nuclear relationship with France.

Simon Bowen, chair of Great British Nuclear, the public body responsible for the delivery of new projects, said the UK would need “at least another couple” of large nuclear power stations after the two currently in development by French state-owned power company EDF.

But he added that a “pause” was needed before the UK decided on what technology to use in those future large plants, which will form part of the country’s drive to meet its net zero goals.

“I think from a value-for-money perspective, we’ve got to pause and look and just check that we’ve got our strategy right,” he said.

The UK is planning to build a mix of large nuclear power plants alongside a fleet of a new type of smaller reactors, a nascent technology with several designs under development, as part of its strategy to decarbonise its electricity grid.

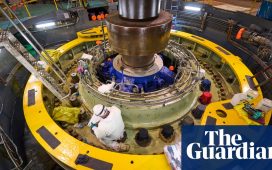

French state-owned EDF is leading the project to build the UK’s first large nuclear plant in more than 30 years — the 3.2GW Hinkley Point C in Somerset — using its European Pressurised Reactor technology but its construction is beset by spiralling costs and delays.

The French utility is also jointly developing plans with the British government to build a second 3.2GW power station using the EPR design at Sizewell in Suffolk.

“I think it’s well recognised, we just need to pause for breath now and . . . [ask] what is the strategy? Is the strategy another two EPRs. Or do we look elsewhere in the market?” Bowen said.

His comments are likely to be a blow for debt-laden EDF, which wants to continue exporting the technology around the world.

Bowen said other technologies worth considering included the AP1000 reactor by Westinghouse of the US, which has already been through the lengthy and rigorous UK regulatory process, as well as rival South Korean and Canadian designs.

But he acknowledged that as the UK was building two EPR-based plants there was a good case for using the same design.

“They may well be [EPR] but they may not be . . . There’s the argument about replicating and bringing costs down, versus the difference in design and whether one is simpler and cheaper or not.”

EDF, which declined to comment, has been pressing the British government to help it fund cost overruns on Hinkley Point C. Earlier this year, the French utility said the price tag could hit £46bn and would not be running until 2029 at the earliest. This compares with a budget of £18bn in 2016 with an operational date of 2027.

Contractually, EDF should pick up any cost overruns on the plant in Somerset in contrast to Sizewell C where the risk has been shifted on to households through their energy bills, with the UK government looking to bring in outside investors to help finance the project.

Great British Nuclear was set up by the government last year to help the country hit its net zero target by 2050, which includes having 24GW of nuclear generating capacity operational by that date. All but one of Britain’s current fleet of nuclear power plants are set to close by the end of the decade, leaving a gap of about 16GW, once the new plants in Somerset and Suffolk are built.

Bowen said he expected a big part of that gap would be filled by a fleet of so-called “small modular reactors” (SMRs). Great British Nuclear is running a competition that could see it invest up to £20bn alongside the developers of two winning designs from a shortlist that includes bids from the UK’s Rolls-Royce, EDF, Westinghouse and another US rival GE Hitachi.

The next stage of the competition closes in June. Bowen said he was aiming to have the first SMRs operational by the mid-2030s, slightly later than the “early 2030s” date given by then-energy secretary Grant Shapps last July.

SMRs have attracted huge interest from governments around the world, eyeing them as key sources of low-carbon power to cut emissions. Promoters claim their modular design would make them relatively quick and cheap to build, avoiding the cost blowouts and delays that have plagued large nuclear projects.

But critics have warned against relying too much on the nascent technology. “One of the biggest problems for SMRs is that they don’t exist,” said Allison Macfarlane, director of the school of public policy and global affairs at the University of British Columbia and a former chair of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

“We’re still at the paper stage, the computer model stage. To get to demonstration models and then a full-scale model when you are ready to commercialise will take billions of dollars,” she added.

Unlike some proposed SMR technology, the developers shortlisted in the UK competition have based their designs on established reactor technology using water cooling systems and standard fuels.

Bowen, who was previously head of Babcock International’s nuclear division, which maintains the British navy’s fleet of nuclear-powered submarines, said he was “very confident” the miniaturised technology would work in the civil power sector.

But he admitted there was less certainty about the costs and timeframe involved in getting the first ones operational. He said the UK would need between 10 and 50 SMRs, depending on their output — the shortlisted designs have a generating capacity of between 300MW and 500MW — and how many large-scale plants were built.